Summary

As the US and China balance between the pursuit of strategic security interests and ambitions to attain economic growth, novel sources of risk are emerging for globally active businesses, ranging from sanctions to export controls.

The Biden presidency will offer only moderate respite from the escalation of this geoeconomic rivalry, even as US-China trade recovers in the aftermath of the pandemic.

In the face of US-China rivalry, the EU and its member states have opted for the third way of “open strategic autonomy”, including a range of trade instruments that will allow the EU to support the competitiveness of its companies more effectively.

European companies need to closely monitor their risk exposure in various transmission channels and stay attuned to unexpected opportunities that can materialise in the form of market entry possibilities and the development of new niches.

INTRODUCTION

The United States and China are economically interdependent, yet their strategic interests pull them apart. After decades of closer Sino-American economic relations, the USA and China have increasingly resorted to geoeconomic rivalry. Despite US hopes for reforms and economic liberalisation in China, the two continue to subscribe to different varieties of capitalism and political organisation. Economic and ideological divergence has spilled over into systemic tensions in the field of national security. Decision-makers in Washington DC, Beijing and Brussels have acknowledged the risks, such as possible raw material shortages, stemming from globally interconnected supply chains. As a result, global powers are seeking to actively reduce economic dependence on each other, in what the EU has termed striving for ‘strategic autonomy’. The states’ objective of seeking greater economic self-sufficiency is now apparent through concrete trade policy measures that increasingly influence the way companies can do business.

This Briefing Paper lays out the key drivers and policy instruments of US-China competition, and their implications for global and European businesses, concluding with a set of possible interventions for the EU to turn geoeconomic risk into strategic opportunity.

US-CHINA RIVALRY: THE BACKGROUND IN BRIEF

The dual imperatives of money and security have given rise to considerable geoeconomic rivalry that plays out in parallel with the interdependence. The US has traditionally wielded global political power through a combination of economic and military might, innovation advantage, as well as democratic norms and institutions. In 2000, President Clinton characterised China joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) as a win-win decision that would bring about the “right kind of change in China”.[1] Yet as China’s economic might grew alongside global trade integration, it became increasingly clear that a level playing field of equal rules and standards for foreign companies would not materialise across the Chinese economy. Instead, some US companies struggled to gain a competitive advantage in China due to what they saw as market distortions and unfair government actions. President Xi Jinping has taken some measures to liberalise outward investments, introduce national fiscal reforms, set up free trade zones to test run economic liberalisation, and take antitrust actions against fintech giants Alibaba and Tencent. Yet in the Western view, these measures have fallen short. According to critics, the WTO principle of national treatment – affording foreign firms equal treatment to domestic players – has not been universally applied. Chinese firms continue to have a competitive advantage with tax breaks, subsidies or other indirect forms of support. Foreign competitors continue to struggle to succeed without local partners or joint ventures, suffer from data localisation requirements in China, and grapple with unfair practices around intellectual property rights and forced technology transfers.

As American businesses have grown weary of the slow pace of reforms in China, the intelligence and strategy voices calling for stronger measures to safeguard national security have gained more traction in the US political arena. The Trump presidency furthered the focus on security and geopolitical rivalry, not least with a range of trade measures that claimed to protect US national security (Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminium), rein in Chinese technology companies, and rebalance the persistent US trade deficit vis-á-vis China. President Biden’s election has brought only moderate respite in the form of reinvigorated bilateral trade and economic dialogue and the reversal of some of the Trump-era specific executive orders (e.g. the attempt to ban WeChat and TikTok), but on the whole China-US trade relations continue to be steeped in rivalry.

In 2021, China surpassed the US for the first time as the world’s top destination for foreign direct investment (FDI) and is set to overtake the US on research and development (R&D) spending by 2025. The deployment of fifth generation (5G) wireless and technology standard-setting has impelled trade partners to select sides, accelerating the decoupling or loose coupling in the industry between regional economies. The preceding trade war, which sought to bolster US dominance and undermine the rival, has resulted in higher costs and business uncertainty for companies in the US and China; and knock-on effects on European companies through trade diversion and cumulative tariff increases along the value chain. This emerging geoeconomic competition can be viewed as the antithesis of the ideal of cooperative and liberal interdependence, prevalent in the preceding decades.

MAPPING OUT GEOECONOMIC RISKS

Geoeconomic risks emerge when states use economics or trade to advance power political objectives or, more specifically, when states impose specific policy measures or instruments of “superpower competition” in order to achieve national objectives. Three main trends are driving the emergence of geoeconomic risks.[2]

First, the securitisation of the economic policy is rooted in the view that global interdependence has crucial national security implications. Previously separate domains of economic and security policy have become intertwined. On the one hand, global economic networks are becoming more centrally managed, as states seek to influence areas from competition to data flows. On the other hand, economies have become increasingly privatised as companies command much of the production and supply of critical infrastructures and emerging technologies. In contrast to the free trade logic of the neoliberal order, superpowers now seek to secure their economies by introducing export controls, investment screening regulations, production or data localisation requirements, or unilateral tariff hikes. This implies a shift to a new geoeconomic order, whereby states focus on security concerns, over mere economic benefits, and on the relative, as opposed to absolute, gains over one another.[3]

Second, the balkanisation of the economy refers to the decoupling of technology and supply chains as states seek to assert their dominance in key sectors. Technocratic measures such as technical regulations, standards and conformity assessment procedures have now emerged as a means of furthering national objectives and strategic interests.

Third, weaponisation of the economy reflects the states’ increasing use of extraterritorial instruments to assert dominance and prompt firms to choose sides. The USA and China have resorted to sanctions, blacklists and financial controls in a manner that undeniably encroaches on market forces and makes it more difficult to do business.

In response to these drivers, the USA and China, as well as increasingly the EU, have resorted to an innovative menu of instruments touching upon trade, competition and anti-trust, industrial policy, development cooperation, financial regulation, or even education and culture.[4] Each instrument may serve a domestic policy objective, but also incurs risks for global business operations (e.g. data collection/cyber network restrictions), company reputation (e.g. association with Xinjiang), and trade financing (e.g. export credits, fintech/digital payments). These “geoeconomic risks” come on top of the existing systemic risks that range from climate disasters to global pandemics.

A key question in mapping out US-China geoeconomic risks is what the underlying objective behind the measure is; and whether the measure is motivated by power politics or a domestic goal such as boosting employment and attaining cheaper inputs. For instance, the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminium were imposed by the Trump administration in the name of national security, but according to commentators served to protect domestic steel jobs. Any measure may serve multiple goals and cater to different interests. While unearthing states’ motives may not always be possible or feasible, several US-China measures have clearly been rooted in great-power competition. The section below presents the most prominent recent examples of trade and economic instruments, the power political objective sought, and their implications in terms of corporate geoeconomic risk.

THE POWER POLITICAL LOGIC OF US-CHINA TRADE IRRITANTS

Sanctions are among those policy tools that most clearly have a strategic and extra-territorial purpose. The US has sought to influence undesirable behaviour by, for instance, issuing the Specially Designated National and Blocked Persons List, featuring several Chinese individuals and entities. In 2021, more Western countries joined in with sanctions over human rights violations against the Uighur minority. China has retaliated with parallel lists of sanctions, and in June 2021 issued a broad-based anti-foreign sanctions law that seeks to counteract foreign measures it deems unjustifiable. As a result, companies may find themselves forced to choose between jurisdictions, and ultimately where and with which suppliers they do business. After H&M expressed concerns over forced labour in cotton production in China’s Xinjiang’s province, it witnessed a considerable drop in sales due to a Chinese consumer backlash.

Meanwhile, the US-China rivalry has resulted in an expanded use of export controls on the grounds of national security and strategic autonomy.[5] Export controls regulate exports of goods, software or technologies (e.g. via authorisations or licensing requirements). They are typically imposed for dual-use items that have both civilian and military applications, or that can be used to produce weapons of mass destruction. For instance, licences can be required for exports to the Chinese telecommunications equipment maker Huawei and the chipmaker Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC). In 2020, China’s own export control law entered into force. The law seeks to control exports of dual-use goods, military products, technologies (e.g. for artificial intelligence or self-driving vehicles), services and items that could be related to national security. Exporters must obtain licences for export-controlled items. The law applies extraterritorially, so that European importers and re-exporters, for instance, need to screen their business partners against the requirements of the export law. The resulting interplay between export controls, blocking statutes and updates to entities lists requires increased compliance efforts from globally active businesses.

The next geoeconomic battle is likely to play out over industrial subsidies, a long-term trade irritant between the US and China. WTO rules have thus far failed to systematically rein in the asymmetric forms of state support for domestic industries, and re-negotiation of the underlying agreements appears unlikely. Thus, global powers are more likely to resort to unilateral measures. The US could launch an investigation into China’s subsidies and their impact on the US economy under Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act, which was a central item in the arsenal of President Trump’s trade war against China. The US holds that industrial subsidies of various forms (e.g. low-cost loans, energy subsidies) have bolstered the competitiveness of Chinese critical industries (e.g. steel, glass, paper, auto parts). The US may continue with Section 301 investigations into unfair trade practices. The EU has also identified a regulatory gap in its capabilities to address non-EU countries’ subsidy practices, and shield its businesses from unfairly attained competitive advantages. As a result, the EU has submitted a proposal for an instrument to tackle distortions from foreign subsidies in its internal market. The instrument could also apply to situations where, for instance, a Chinese company that has received financial contributions from the state attempts to merge with or acquire a European firm.

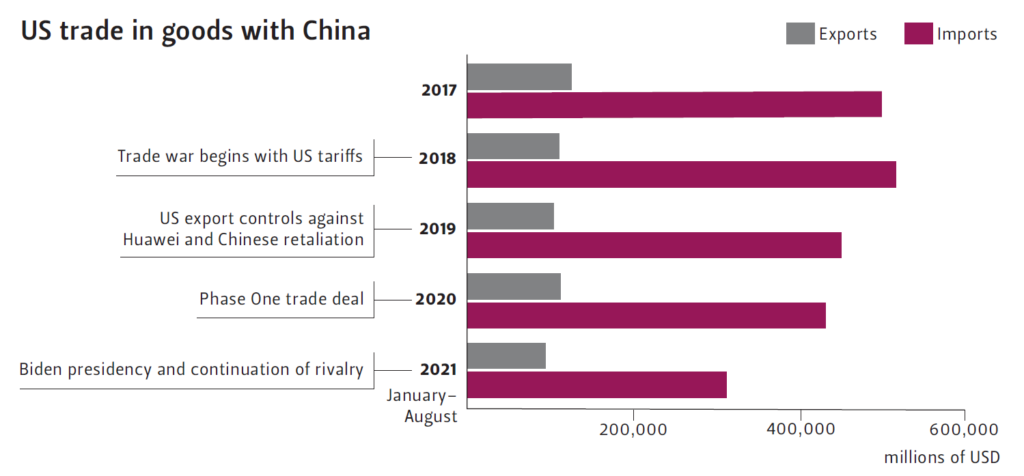

However, behind the tough rhetoric and retaliation through carefully selected geoeconomic policy instruments, in numerical terms, US-China trade is recovering (see Graph 1). The onset of the US-China trade war in 2018 raised significant concerns over the effects of geoeconomic rivalry on bilateral trade. In 2020, the US and China committed to a “Phase One” agreement to increase purchases of certain goods by USD 200 billion over the course of two years. While US officials consider that China is falling short of the target, in 2021 China will be slightly closer to meeting the commitments, compared to 2020. US export expansion vis-à-vis China has also been driven by China’s early recovery from the pandemic, as well as exports of oilseeds and grains (soybeans), oil and gas, as well as semiconductors and components. Currently, economic growth, not tariffs or policy instruments, stands as the primary driver of US-China trade. China continues to represent a major growth market for American companies. The spending power of Chinese consumers is growing, and there are regulatory benefits to maintaining local presence. While select US company announcements, such as the May 2021 decision by Tesla to postpone the expansion of its production facilities in Shanghai, show that US-China decoupling may be underway, the prevailing mood leans towards the expansion of investment and presence in China.

Yet, as US-China bilateral trade grows, the politically sensitive US trade deficit with China is also likely to increase. US imports from China continue to grow in line with consumer demand. The US surplus in services has been depressed by the pandemic, due in part to a collapse in international tourism, including among Chinese consumers. This is likely to prompt US decision-makers to continue with further measures seeking to rival China, which in turn may have a larger impact on US-China trade. In October 2021, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) signalled a potential return to the process of tariff exclusions, whereby the administration grants waivers for imports from China when the importer has, for instance, no alternatives available elsewhere, or is prone to a disproportionate economic burden due to the tariffs. Notwithstanding a softer rhetoric, the Biden administration exhibits a significant degree of continuity with the Trump administration.

CONCLUSIONS: IMPLICATIONS FOR EUROPE

In terms of political actions, US-China geoeconomic competition will continue and potentially strengthen under the Biden administration. For the EU and its member states, including Finland, the rivalry has come with spillover effects. On the one hand, some EU exporters (namely those exporting electrical machinery or chemical products) have been among the main beneficiaries of trade diversion in the face of a falling market share of Chinese imports.[6] On the other hand, EU manufacturers, such as motor vehicle or transport equipment manufacturers, who rely on intermediate inputs in their value chain, suffer from the cumulative effect of US-China tariffs. In this context, the EU has sought to take the third way by focusing on “open strategic autonomy”. To improve openness, the EU has continued to push forward bilateral trade agreements with Latin American and Asian partners. With China, it negotiated the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), but the tensions over human rights in Xinjiang quickly escalated into two-way sanctions, putting the CAI on hold. To strengthen strategic autonomy, the EU has sought to safeguard supply chain resilience and improve self-sufficiency in critical raw materials. The reinvigorated proposal for an international procurement instrument seeks to level the playing field vis-à-vis China on government procurement, a major area of national economy. New sectors will be added to the foreign direct investment screening regulation that seeks to rein in Chinese takeovers of EU firms. The EU is also creating a new instrument to deter and counteract coercive actions by third countries, such as China’s manipulation of prices in the manufacturing industry and the exclusion of EU companies from public tenders; or the US sanctions on companies involved in building the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. The instrument would empower the EU to apply trade or investment restrictions towards a third country interfering with the EU’s policy space. In practice, the instrument could serve more as a deterrent of last resort, and would likely be used mainly in instances where coercion has clearly breached international law.

At the same time, EU-US cooperation is increasing in critical areas, such as technology, industrial subsidies, or the multilateral trading system. The EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC) could pave the way for the adoption of common principles on export controls, cooperation on artificial intelligence and semiconductor supply chains, and exchanges of information on investment screening. Shared approaches or standards could eventually be expanded to other trade partners. Cooperation in global standard-setting bodies is more crucial than ever to ensure that standards do not diverge further following the logic of path dependence. The EU will continue to advocate reforming the multilateral trading system, embodied in the WTO, to mitigate the escalation of large-scale geoeconomic trade tensions. A restoration of the two-step dispute settlement mechanism could ensure that geoeconomic rivalry does not escalate into political and security conflict.

In the meantime, private sector actors will need to better quantify and map out the geoeconomic risks they face alongside other systemic risks to operational models and earning potential. Companies need to strengthen their supply chain due diligence, sharpen the contractual clauses, and stay attuned to trade policy changes. Companies are starting to learn to identify business opportunities, such as windows for market entry, new avenues for government support, or chances to capitalise on diverging trade triggered by a host of new trade instruments. For instance, a coalition of US business groups are on the path to securing USD 52 billion in funding for semiconductor manufacturing under the US Innovation and Competition Act. European mining and metallurgy players are innovating responsible business practices as a means of differentiating themselves on the global playing field. The European battery industry has launched recycling and metal recovery initiatives with the support of French government funding. Public and private actors are collaborating to build a federated and secure data infrastructure based on principles of sharing and openness, as opposed to market concentration. The responses from European companies to the new geoeconomic order often serve the dual objective of enhanced resilience and improved sustainability. At the same time, public authorities in the EU must expand the support available to businesses to navigate the new compliance and trade challenges. Such initiatives could help European companies flourish, and mitigate the emerging context of geoeconomic great- power rivalry.

ENDNOTES

[1] See the White House Office of the Press Secretary, ‘Remarks by the President on administration efforts to grant China permanent trade relations status’, 2000. https://1997-2001.state.gov/regions/eap/000110_clinton_china.html.

[2] See Christian Fjäder, Niklas Helwig and Mikael Wigell, ‘Recognizing “Geoeconomic Risk”: Rethinking Corporate Risk Management for the Era of Great-Power Competition’, FIIA Briefing Paper 314, 2021. https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/recognizing-geoeconomic-risk.

[3] See Anthea Roberts, Henrique Choer Moraes and Victor Ferguson, ‘Toward a Geoeconomic Order in International Trade and Investment’, Journal of International Economic Law, Volume 22, Issue 4, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgz036.

[4] See Henrique Choer Moraes and Mikael Wigell, ‘The Emergence of Strategic Capitalism: Geoeconomics, Corporate Statecraft and the Repurposing of the Global Economy’, FIIA Working Paper 117, 2020. https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/the-emergence-of-strategic-capitalism.

[5] See Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, ‘China and the United States – A challenge to companies: Impacts of the superpower competition to Finnish companies’, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland and Confederation of Finnish Industries Joint Project Final Report, 2021. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-281-372-5

[6] See Moody’s Analytics, ‘Trade Diversion since the US-China Trade War’, Analysis, 2020. https://www.moodysanalytics.com/-/media/article/2020/trade-diversion.pdf.