Sammanfattning

Free movement within the Schengen Area has been challenged in recent years by national measures: from internal

- Free movement within the Schengen Area has been challenged in recent years by national measures: from internal border checks after the ‘migration crisis’ to the closure of borders in the Covid-19 crisis.

- This is the first time in the history of Schengen that member states have categorically refused entry to other EU citizens who are not registered residents or cross-border workers.

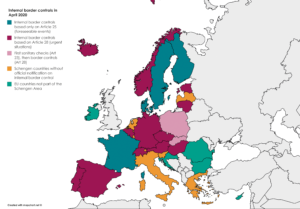

- Seventeen Schengen countries have submitted a notification on reintroducing internal border control due to Covid-19: Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain and Switzerland.

- The use of Schengen provisions was creative: 12 states justified their internal border controls as a case requiring immediate action (Art. 28), France and Denmark expanded their already existing internal border controls (Art. 25), Finland appealed to the ‘foreseeable event’ clause (Art. 25), and Slovakia and Poland introduced ‘healthcare-police measures’ (Art. 23) before launching border controls (Art. 28).

- The crisis illustrates the need to reform Schengen in order to maintain the legitimacy of commonly agreed rules.

Introduction

Free movement is a fundamental aspect of European integration. It has expanded from the right to free movement of workers in the European Coal and Steel Community (1952) to EU citizens’ right to cross borders without passport control in the Schengen Area. The Schengen Area took effect on 26 March 1995 when Belgium, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal officially removed internal border controls between the countries.[1] When we look at Schengen 25 years later, in spring 2020, the vision of a borderless Europe seems to have experienced a serious setback. All 26 Schengen countries[2] have temporarily closed their external borders and 18 countries are conducting internal border checks, 17 of them due to Covid-19. Several countries have even set up domestic ‘border controls’ by sealing off certain regions within their country in order to curb the spread of Covid-19. Lorry tailbacks have been reported at European internal borders and EU citizens are struggling to return to their home countries. While the scale of the current restrictions is unprecedented, migration pressure since 2015 has already challenged the functioning of the Schengen system as six countries (Germany, France, Austria, Sweden, Denmark and Norway) have conducted border checks for much longer than allowed by the Schengen Borders Code.

This Briefing Paper discusses the reasons for and implications of internal border controls established in order to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. It will outline and analyse border controls established before the current Covid-19 situation and in relation to it, and the impact of Covid-19 on the Nordic Passport Union. The paper will conclude with an assessment, which suggests that the re-imposition of border controls in light of the current and past crises speaks for a significant degree of flexibility within the EU rules on borders, while the imposed Covid-19 measures will further highlight the need to consider Schengen reforms.

It is important to note that although borders in the Schengen Area are closed, EU citizens’ formal right to free movement remains. EU citizens residing in another EU country do not have to leave their country of residence, suggesting that the right to free movement has de facto become the right to stay put. The Free Movement Directive (2004/38/EC) grants all EU citizens the right to reside in any EU country for three months without registration. After that, they have to demonstrate that they are working, studying, applying for work or have the means not to become a burden on the social security system of the state of residence. In addition to public policy and public security, the Free Movement Directive allows restrictions based on public health, primarily in the case of diseases ‘with epidemic potential as defined by the relevant instruments of the World Health Organisation’ (Article 29(1)). On the basis of public health, countries could restrict the entry of EU citizens into a country or expel an EU citizen that has resided for less than three months in the country, but such expulsions have not been publicly reported. Even though the right to free movement remains formally unaffected, this is the first time in the history of Schengen that EU citizens have been categorically prevented from crossing European borders.

Schengen rules challenged even before Covid-19

The Free Movement Directive regulates people’s right to free movement, which in practice refers to the right to reside in other EU countries (not formally affected by Covid-19). The Schengen Borders Code (SBC, Regulation 399/2016), in turn, stipulates conditions on border controls, such as the temporary reintroduction of internal border controls. The SBC entered into force on 13 October 2006. It allows internal border controls only in cases threatening public policy and the internal security of a state, but not all identity checks are considered internal border controls. Article 23 allows countries to conduct police checks inside the territory, provided that they do not have border control as an objective. Such controls do not have to be reported to other member states. In contrast, if a country decides to launch actual border controls at internal borders, the SBC provides three legal bases, which all require a notification.[3] Article 25 of the SBC allows the reintroduction of borders in foreseeable events, in which case the notification should be submitted at least four weeks in advance, or later if the circumstances become known later. Based on Article 25, countries may first reintroduce border controls for 30 days and prolong them for up to six months. Article 28, in turn, allows countries to reintroduce border control in cases requiring immediate action, with controls possible initially for 10 days, and thereafter for periods of up to twenty days for a maximum of two months. In a situation putting the overall functioning of the Schengen Area at risk, Article 29 provides the Council with the opportunity to recommend that certain countries reintroduce internal border control for a maximum of six months, a period that is renewable three times.

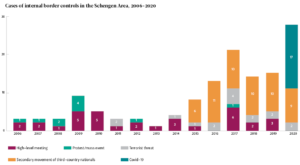

As shown in Figure 1, a turning point in the internal border controls was the so-called migration crisis in 2015, since which time six Schengen countries (Germany, France, Austria, Denmark, Sweden and Norway) have had internal border controls in place at specific border-crossing points either based on the large influx of third-country nationals, or on a terrorist threat in the case of France.[4] The countries first established border controls as cases requiring immediate action (Article 28), but after the two-month deadline, they had to shift to Article 25, which allows a six-month period. France has systematically referred to the terrorist threat in all of its notifications since the border controls were first established after the terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015. The other five countries could make use of the Council recommendation based on Article 29 from May 2016 to November 2017. Since then, all countries have submitted a notification of prolongation every six months, appealing again to Article 25. According to Deutsche Welle, a representative of the German Interior Ministry interpreted that the lime limits would be reset every six months and apply only to each specific notification.[5] However, there is no such mention in the Schengen Borders Code. This ignorance of the maximum periods undermines the legitimacy of the Schengen acquis, especially as the member states have not been able to reach a position on the Commission proposal issued in September 2017 to amend the Schengen Borders Code either (COM(2017) 571 final).

If countries do not follow EU rules, measures can be taken. The Commission monitors compliance with European legislation and may launch an infringement procedure and eventually refer the issue to the European Court of Justice. The monitoring of the Schengen Borders Code, however, is additionally regulated by a lex specialis, a Regulation on the Schengen Evaluation Mechanism, where compliance with the Schengen acquis is evaluated annually in 5–6 states. Since the Schengen Evaluation Mechanism was implemented in November 2014, only one infringement procedure related to the Schengen Borders Code has been launched, concerning Estonian conditions for crossing external borders. The Schengen Evaluation Mechanism seems to have de facto come to replace infringement procedures.

Since the migration crisis, annual reports related to the Schengen Evaluation Mechanism have not been published. The European Parliament has, however, drafted their own reports on the functioning of the Schengen Area: in May 2018, the EP called on the Commission to launch infringement procedures in cases of violations. However, the Commission does not seem to consider the violations of the SBC serious enough, albeit encouraging the countries to lift their internal border controls. For example, the political guidelines of the new Commission expected a ‘return to a fully functioning Schengen Area of free movement’.[6]

In brief, member states have had much leeway in the application of the internal border controls even before Covid-19, by combining different legal bases and ignoring the maximum periods outlined in the rules.

Closure of Schengen borders in the Covid-19 crisis

The Schengen Borders Code does not allow the reintroduction of internal border controls due to public health, but the Commission and most of the member states seem to regard the coronavirus as an internal security threat as well. In its COVID-19 guidelines for border management measures, the European Commission outlined that ‘In an extremely critical situation, a Member State can identify a need to reintroduce border controls as a reaction to the risk posed by a contagious disease’.[7] While aiming to slow down the spread of the disease, internal border controls may also constitute a way to prevent people from stockpiling in the neighbouring country, from seeking medical help or even from temporarily relocating to regions where coronavirus cases are fewer.

Due to the spread of the coronavirus, 17 countries in total submitted a notification on internal border controls. Of these, 14 countries (apart from Finland, France and Denmark) appealed to Article 28 of the Schengen Borders Code, which allows the countries to immediately establish temporary border control in ‘cases requiring immediate action’. Among the six countries that have already conducted border checks since the migration crisis, three notified that they were closing their borders based on Article 28 (Germany, Austria and Norway) and two on extending their existing controls to all internal borders (Denmark and France). Sweden, in turn, has not submitted any further notifications, but is continuing the existing random border checks based on a terrorist threat (Article 25) at least until May 2020. The countries that appealed to Article 28 could initially establish border controls for 10 days, but all of them have already notified about prolonging their controls at least until early May.

Some countries have also referred to their border controls simply as health checks, which the countries do not have to report to the Union, as also notified by the Commission in their guidelines mentioned above. Poland and Slovakia initially launched sanitary controls only, but later notified that they would also conduct internal border controls. Poland only provided a notification on sanitary checks without referring to a provision of the SBC, but the Slovak delegation referred to Article 23 of the Schengen Borders Code, which allows the member states to conduct police checks within the country. It is possible that other countries also regard their border checks as health checks only, which means they do not have to notify them to others nor observe any maximum periods for the controls. Checks of this sort may better ensure the movement of goods and hence the functioning of the Single Market.

Unlike Germany, Austria and Norway, Denmark and France did not appeal to the Urgency Article to introduce new controls based on Covid-19, but only notified that they were extending their existing controls (based on Article 25) to all internal borders. All five countries have notified that they would be continuing their checks until October/November 2020, and Sweden also considered prolonging its (non-corona-related) checks until November 2020. Finland was the only new country to appeal to Article 25, which refers to foreseeable events. On the basis of this, a country may reintroduce internal border controls for an initial 30 days and thereafter for up to six months. Finland first reintroduced the border controls for one month and then prolonged them for another month, until 13 May. One of the benefits of the Foreseeable Events Article is that a country does not have to submit new notifications every few weeks. Finland may also prolong the controls for up to six months, while the other states can no longer appeal to Article 28 after two months of internal border controls. Overall, this flexibility in appealing to Articles 23, 25 and 28 while conducting similar checks illustrates the ambiguity of the legal provisions on internal border controls.

After the reintroduction of the internal border controls, problems have been reported concerning the cross-border movement of goods and EU citizens attempting to return home from other EU countries and third countries. The Commission has urged member states to tackle these issues. The Commission has prompted the member states to establish green lanes for freight transport, and has issued other recommendations to facilitate the flow of goods and guidelines to facilitate the movement of frontier workers practising critical occupations. The Commission has also lamented the observed disruptions, such as waiting times in excess of 24 hours at certain borders. Furthermore, while speaking at the European Parliament, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen criticised the decisions by member states to reintroduce internal border controls: ‘A crisis without borders cannot be resolved by putting barriers between us. And yet, this is exactly the first reflex that many European countries had’, while also reporting that the Commission had ‘intervened when a number of countries blocked exports of protective equipment to Italy’.[8] National leaders have pledged to follow the Commission’s guidelines, but not one country has set a date as yet for giving up internal border controls.

Member states now categorically refuse entry to EU citizens, with some exceptions. In their notifications, some countries specified that nationals, residents, cross-border workers, duly accredited persons, and those ‘who demonstrably cross internal borders on a regular basis’ are allowed to enter, as well as members of diplomatic missions, and that the movement of goods would be allowed in accordance with the recommendations of the Commission. In addition, Czechia mentions, for example, an integrated rescue system, people in the event of an unforeseen emergency, and freight transport.[9] Non-EU Schengen state Switzerland, in contrast, outlined that only people with professional reasons or those in a situation of extreme necessity would be allowed to pass.[10] Many citizens in the border regions no longer have the possibility to work, do their grocery shopping or visit their families on the other side of the border. This is particularly striking in the northern border regions between Finland, Sweden and Norway, with almost 70 years of open borders.

The 70-year-old Nordic Passport Union’s first disruption

Three of the five Nordic states closed their internal borders due to Covid-19: Finland, Norway and Denmark. Norway and Denmark (as well as Sweden, which has not closed its internal borders thus far) already had internal border checks at some of their border-crossing points, but for Finland, the decision to close the internal Schengen borders with Sweden and Norway was historic. The Nordic countries have formed the borderless Nordic Passport Union since 1952, and this is the first time in almost 70 years that Finland’s borders with Sweden and Norway have been closed, allowing only absolutely necessary travel. According to the Nordic Passport Convention (1979), when necessary in international or national circumstances, all states can stop applying the agreement with one or several states, but they must immediately inform the other states. Simply enough, each Nordic state becomes automatically informed when a country informs the other Schengen states.

Cross-border commuting has been common across the Nordic borders, and the Northern borders of Finland still allow border-crossing for essential work. The Finnish government, however, banned regular commuting between Finland and Estonia, which is not a Nordic country. The Government decided to allow some exceptions for cross-border commuting in the land borders with Sweden and Norway, where daily travel for work is common. Finnish healthcare workers may continue to work on the Swedish side of the border, and Sweden has committed to providing hospital and intensive care capacity for Finnish patients.[11] The closure of the borders came as a major blow to the northernmost regions in particular, where the border has seemed almost non-existent. Although people understand that the situation is highly exceptional, reintroduced border controls may permanently damage people’s trust in fluent border-crossing and in the opportunity to lead a life on both sides of the border.

The need to reform Schengen after Covid-19?

National reactions to the Covid-19 situation show that Europe may not be as united as people would like to believe. As described above, Commission President von der Leyen lamented internal border controls as a first reflex to the Covid-19 crisis, but problems in finding common ground have been evident at least since the so-called migration crisis, which had already been noted by Commission President Juncker in his State of the Union Address in 2016.[12] In crisis situations, internal border controls may attempt to show national citizens that something concrete is being done, to show neighbouring countries that they should control who they allow to pass, and to put pressure on the Union to find a common approach. The price, however, is that the ambiguous use of the legal provisions undermines the legitimacy of Schengen.

In one sense, the coronavirus has reopened the wounds of both the financial crisis and the migration crisis: we can observe the North-South divisions of the financial crisis in the debates over possible ‘corona bonds’, while at the same time countries are closing their borders instead of taking a European perspective. This crisis, however, affects all countries more symmetrically than the migration or financial crisis. In this sense, there may be better chances of finding common ground and a sense of solidarity. In addition, despite the rather gloomy picture that internal border controls draw of nation- centeredness in times of crisis and the creative application of the Schengen rules, we need to remember that the European Union not only concerns borders, or the lack of them. The right to free movement has not disappeared, although people may not be able to cross EU borders for a while. Eventually, the crisis could even increase the appreciation of free movement, since we can now see what a Europe with closed borders would look like.

Previous crises have tended to prompt European integration to move forward, and the Covid-19 crisis has already demonstrated the need for more coordination in preparing for epidemics. Once the situation is eventually settled, the Covid-19 situation may also serve as a push to reform Schengen. In the end, if member states want to maintain Schengen as the first issue to compromise over in times of crisis, the rules should allow such decisions to be made without ambiguous interpretations on the provisions of the Schengen Borders Code. The Commission, although not intervening in previous violations of the Schengen Borders Code, has been active in providing Covid-19 ‘guidelines’ for the member states in their procedures concerning internal and external measures. These guidelines could serve as a basis for reforming Schengen to better adapt to epidemic situations in the future. European rules are the result of difficult negotiations among all countries and the Union cannot afford to undermine the duty to comply with those rules in a uniform manner. Otherwise, such rule-stretching may spread to other fields as well.

Endnotes

[1] France actually extended its border controls for another year, citing security threats related to the 1995 bomb attacks in Paris. See e.g. Siebold, Angela (2013), Between Borders: France, Germany, and Poland in the Debate on Demarcation and Frontier Crossing in the Context of the Schengen Agreement. In Arnaud Lechevalier and Jan Wielgohs (eds.), Borders and Border Regions in Europe – Changes, Challenges and Chances, 129–144, Bielefield: Transcript Verlag.

[2] Out of the current EU member states, Ireland is the only country that has a permanent opt-out from the Schengen acquis, whilst the most recent EU member states, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania and Cyprus, have not yet been accepted into the area. The Schengen Area also includes four countries that are not part of the EU: Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

[3] The notification should be submitted to the European Commission and other member states, and such documents are made publicly available in the online document register of the EU Council: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/documents-publications/public-register/ (accessed 26 March 2020).

[4] On the previous internal border controls, see e.g. Ceccorulli, Michela (2019), Back to Schengen: the collective securitisation of the EU free-border area, West European Politics 42(2), 302-322; Evrard, Estelle, Nienaber, Birte & Sommaribas, Adolfo (2018), The Temporary Reintroduction of Border Controls Inside the Schengen Area: Towards a Spatial Perspective, Journal of Borderlands Studies.

[5] Schacht, Kira (2019), Grenzkontrollen in EU-Ländern stellen Schengen infrage [Border checks in EU countries challenge Schengen Agreement], Deutsche Welle, 13 November 2019, https://www.dw.com/de/grenzkontrollen-in-eu-l%C3%A4ndern-stellen-schengen-infrage/a-51033606 (accessed 1 April 2020).

[6] von der Leyen, Ursula (2019), Political Guidelines for the next European Commission 2019–2024, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/political-guidelines-next-commission_en.pdf (accessed 1 April 2020).

[7] European Commission (2020), COVID-19 Guidelines for border management measures to protect health and ensure the availability of goods and essential services, Brussels, 16.3.2020 C(2020) 1753 final, https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20200316_covid-19-guidelines-for-border-management.pdf (accessed 21 March 2020).

[8] von der Leyen, Ursula (2020), Speech by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary on the European coordinated response to the COVID-19 outbreak, Brussels, 26 March 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_20_532 (accessed 27 March 2020).

[9] Czech Delegation (2020), note 6790/20. Brussels, 13 March 2020.

[10] Swiss Delegation (2020), note 6845/20. Brussels, 16 March 2020.

[11] Finnish Government (2020), Government decided on tightening restrictions on border traffic along the border with Sweden and Norway and on steps to secure medical care in Åland. Available at: https://vnk.fi/artikkeli/-/asset_publisher/hallitus-linjasi-rajaliikenteen-tiukennuksista-ruotsin-ja-norjan-vastaisella-rajalla-ahvenanmaan-sairaanhoito-turvataan?_101_INSTANCE_iemYRQDn9G8r_languageId=en_US (accessed 7 April 2020).

[12] Juncker, Jean-Claude (2020), State of the Union Address 2016: Towards a better Europe – a Europe that protects, empowers and defends. Strasbourg, 14 September 2016.