Sammanfattning

Since the start of Putin’s third presidential term in 2012, geopolitical competition has also become rooted in the Nordic region, and small states’ room for manoeuvre in security policy has shrunk.

In Russia’s view, maintaining ‘good neighbourly relations’ is primarily the responsibility of small states that always need to negotiate the limits of their sovereignty with great powers, such as Russia.

From the Nordic point of view, the relations may require walking on eggshells. Prior to 2014, Norway was often mentioned among Russia’s ‘good neighbours’, but now Russia regularly calls off its policy of ‘reassurance and deterrence’.

There are increasing signs that, in Russia’s view, a ‘good neighbour’ should refrain from extensive security collaboration and training with NATO and the US. Hence, Finland and Sweden cannot wholly avoid political tension with Russia merely by staying outside of the Alliance.

Introduction

The dynamic between Russia and the Nordic states has always reflected the broader Russian foreign policy trends. In the 1990s, several inclusive cooperative frameworks in Northern Europe were established, and Russia became a member of the Council of the Baltic Sea States in 1992, the Barents Euro-Arctic Council in 1993, and the Arctic Council in 1996. In the EU, the Northern Dimension initiative was launched in 1999. Security issues were outside the agenda of these organisations or the agenda concentrated on the softer cross-border security issues such as search and rescue cooperation, environmental, and health-related topics. Common interests and shared values were seen as the basis of constantly expanding cooperation between the Nordic states and Russia.

During the first decade of the 2000s, Russia became politically more reserved about common values and expanding cooperation with the West. The focus shifted from political to economic cooperation. Both in the Nordics and Russia alike, economic collaboration was often seen to score wins for Russia and the Nordic states. Northern Europe was a gateway[1] to and from Russia – harbours, gas pipelines, and Arctic oil exploration were among the topics on which Russia and the Nordic states could find a common tone, even if the political agendas may have clashed.

After Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, the emphasis shifted again, and the economy was increasingly seen as part and parcel of the wider geopolitical agenda. The political rhetoric no longer emphasised win-win solutions and economic interdependence, but was replaced with talk about Russia’s economic and political ‘sovereignty’ – that is, ‘strategic’ independence internally and externally.

The developments in Northern Europe reflect the wider geopolitical competition between the West and Russia. This strengthened geopolitical framing also means that Northern states’ room for manoeuvre is diminishing. As other EU states – especially those in close proximity to Russia – have joined NATO one after the other, Finland’s and Sweden’s non-allied status has become even more strategically important to Russia.

This paper will examine the three Nordic states that have the most active relations with Russia: Finland, Norway and Sweden. Norway is one of the founding members of NATO, but remains outside the EU. Finland and Sweden have both been members of the EU since 1995, but are militarily non-allied. While the security political status of Finland and Sweden is similar, their relations with Russia are rather different: Finland follows a tradition of anticipating Russia’s reactions whereas Sweden is known for its principled and vocal criticism of Russia. NATO member Norway maintains an official policy of ‘deterrence and reassurance’, a mixture of allied cooperation and defensive capability on the one hand, and confidence-building measures towards Russia, on the other.

The paper first examines Russia’s discursive frames for Northern Europe and how they have changed over the years; the primary sources consist of the Russian foreign ministry’s web archive material on bilateral relations between Russia and the Nordic states in 2012–2021. After that, the paper studies the extent to which Russia’s actual policies reflect the discursive framing in the areas of territorial issues, security, and country-specific economic and other interests.

'Good neighbourly relations'

In the Russian context, the Nordic states are commonly seen merely as small states in the wider European context. In Russia’s understanding, small state sovereignty is always relative, and smaller states need to negotiate its practical limits with great powers such as the US, China and Russia.

Reflecting this point, Russian Foreign Ministry statements on the Nordic states between 2012 and 2021 highlight that the Nordic countries and Russia need to maintain ‘good neighbourly relations’. This concept is often explained as ‘mutual respect’ and the ‘observance of principles of international law’ between neighbours. During the Soviet times, ‘respect’ and ‘principles of international law’ meant that outsiders should not interfere in or criticise the Soviet Union’s human rights violations or other aspects of its policies.

Some of this is still ingrained in Russia’s understanding of the concept: open criticism towards its violations of international norms is often met with accusations of ‘Russophobia’, or a ‘destructive’ or an ‘anti-Russian’ approach. These labels are useful because they can be applied to almost any act, as there is no specific criteria for what they mean. Behaving ‘responsibly’ and maintaining trust is primarily the responsibility of smaller neighbouring states. In Russia’s view, ‘constructive’ and ‘pragmatic’ behaviour means that neighbouring countries should fulfil expectations and responsibilities as Russia understands them.

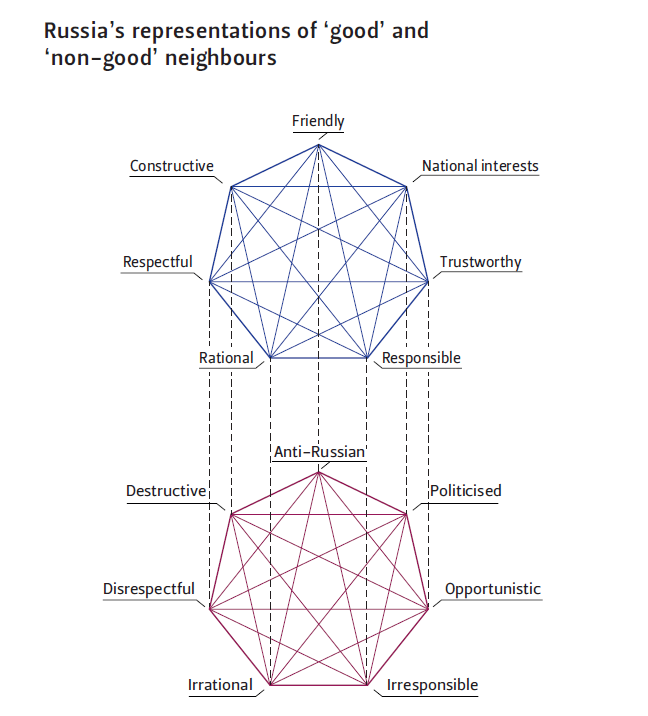

Correspondingly, when a state deviates from a course that Russia prefers, it is accused of unconstructive behaviour that violates – if not legal then at least ‘political’ – obligations towards Russia. Russia claims to merely mirror the choices made by small states: positive, constructive action is reciprocated, whereas destructive policy justifies countermeasures. Figure 1 shows how Russia’s Foreign Ministry uses these signifiers to frame its ideal for bilateral relations with Nordic countries, and its negative counterpart.

Figure 1. Russia’s views on a ‘good’ and ‘non-good’ neighbour.

Source: Authors’ resesarch based on Russian Foreign Ministry’s publication material 2012-2021.

Not surprisingly, out of the three Nordic states examined in this paper, Sweden has traditionally attached the least importance to ‘good neighbourly relations’ with Russia. Not sharing a border with Russia, and not having fought in the Second World War with or against the Soviet Union, makes the relationship less complex and more distant. Norway and Finland both share a border with Russia, and have notably more engagement with the country. Norway has about 200 km of land border and almost 1,700 km of maritime boundary with Russia, while Finland has over 1,300 km of land border.

Norway imposed restrictions prohibiting the deployment of nuclear weapons and permanent allied forces on its territory during the Cold War in order to reduce tensions with Russia. Oslo has also actively developed bilateral cooperation with the Soviet Union and later Russia in areas such as cross-border contacts, resource extraction, and fisheries. The Barents Euro-Arctic Council and the agreement on the delimitation zone in the Barents Sea with Russia in 2010 are some of the great successes of Norwegian post-Cold War foreign policy. Only since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and its increasing militarisation of the High North has Norway agreed to a rotational presence of US marines in central Norway (2017–2020) and the holding of multinational exercises in the High North.

Finland has the closest and most nuanced relationship with Russia. Maintaining good neighbourly relations was a lifeline for Finland after the Second World War, and hence it developed a distinctive version of neutrality where it constantly anticipated Russia’s reactions to its foreign – and sometimes internal – policy moves. Although the relationship with Russia is fundamentally different now, anticipation of Russia’s reactions is reflected in the Finnish foreign policy style. Furthermore, the level of activity and density of political and economic links between Finland and Russia stand out in a Nordic comparison (on economic links, see Figure 2 and 3).

The specific Russian frames and policies towards the respective Nordic country depend on the geography, security political status and specific leverages and vulnerabilities that exist in the country; these fields will be studied one by one below.

Territorial issues

Since the war in Ukraine started and Russia’s foreign policy stances became more assertive and aggressive towards the West, Russia has applied growing pressure on Norway in particular when it comes to territorial issues. The severity of the issues varies from smaller provocations to the outright questioning of sovereign integrity in specific issues.

An example of a smaller provocation was the photoshoot featuring black-listed then deputy prime minister Dmitry Rogozin during a sudden visit to Svalbard in 2015, taking advantage of the Svalbard Treaty signed in 1920 that grants access to a citizen of a signatory state ‘without regard to reason or purpose’.

The Svalbard Treaty grants Norway sovereignty over the archipelago, but also gives all signatories the right to freely conduct commercial activities on the islands. Russia claims that this also extends to the continental shelf – which contains hydrocarbon resources. A more serious move in 2020 involved foreign minister Sergei Lavrov’s letter to his counterpart criticising Norway’s interpretation of the Treaty and claiming that Norway was not putting Russia on an equal footing with others. Russia requested bilateral consultations on the Treaty with Norway – despite the fact that the treaty is a multilateral one. Shortly thereafter, Russia’s general consul in Svalbard cast doubt on Norway’s sovereignty over the islands by claiming that Svalbard was equally ‘Russian land’ because Russian ancestors had also shed blood over it. In 2021, Russia’s Foreign Ministry accused Norway of hidden militarisation of the islands.[2]

In 2015 both Finland and Norway experienced novel challenges in the management of the northern border with Russia. In both cases, Russia changed its established border practices and allowed entry to the border zone without valid documentation for travellers in certain northern border points. Persons were trafficked to the border zone by shady businessmen, while border officials turned a blind eye. Finland bilaterally negotiated a solution to the changed practice with Russia. Afterwards, Russia framed this bilateral deal as a ‘constructive’ way to deal with disagreements, and highlighted the solution as a concrete sign of good neighbourliness between the two countries, although Russia had created the issue itself and there had been no disagreements or problems with the management of the border prior to Russia’s change of practice. Norway, for its part, closed the border point but later negotiated the return of migrants in buses to Russia. Both Norway and Finland belong to the Schengen area, but the incidents served as a reminder of Russia’s bilateral preference.

Security policy is another field where balancing between Russia’s concerns, on the one hand, and national security concerns, on the other, create some dilemmas for the Nordic states.

Nordic non-allied exceptions

All Nordic states are deeply integrated into Western structures economically, politically and security-wise. Occasionally, however, Russia chooses to act as if this was not the case. For instance, when Russian and Finnish foreign ministers met in early 2021, foreign minister Lavrov claimed that the strained relationship between the EU and Russia did not reflect negatively on the relationship between Finland and Russia, which is based on cooperation – as if Finland was not a part of the EU and its decision-making.

Furthermore, Russia has promoted the idea that Finland – and Norway – should act as mediators between the great powers or, with regard to Norway, between its own NATO allies and Russia. Russia has sometimes used these initiatives to advance its own political goals rather non-constructively, however. For instance, President of Finland Sauli Niinistö took up the idea of confidence-building through agreeing to the use of transponders in aviation around the Baltic Sea in his talks with President Putin, firstly in July 2016 and later in a NATO conference in Poland. However, it was Russia that invited individual countries in the region to bilateral discussions on the topic and interpreted the initiative instrumentally through the prism of its own political goals.[3]

Now that Finland has suggested confidence-building measures to revive the “spirit of Helsinki”, there are concerns that Russia may try to use the initiative to tactically advance its own agenda. In December 2021, Putin expressed his support for Finland’s initiative to organise a summit to coincide with the 1975 Helsinki Final Act in the context of its own proposals for “security guarantees” that would divide Europe into spheres of influence.[4] This is certainly not the idea behind the Finnish initiative – which may or may not be known to outside observers.

Good neighbourly relations also have explicit security policy implications in Russian thinking. The Russian ambassador in Finland has noted in an interview that due to the shared border and the past experiences, ‘there is no alternative to good neighbourly relations’.[5] President Putin has also explicitly stated that Finland’s security would be undermined if it decided to join NATO, and claimed that Russia valued Finland’s ‘neutral status’ (sic).[6]

Earlier, Norway was frequently mentioned among the good neighbours of Russia alongside Finland, but tensions in the relationship have been mounting at the same pace as Russia’s challenges towards NATO and the US have become more explicit. In 2017, the US stationed troops in Norway for the first time since WWII. Russia claimed that the 700 soldiers – stationed hundreds of kilometres away from the Russian border – posed a direct military threat to Russia, and criticised Norway for stationing US troops on its territory. When the troops were pulled out in 2020, the Russian criticism nevertheless continued.

Furthermore, Norway’s own measures aimed at developing a defensive capability were enough for Russia to accuse Norway of ‘destabilising the situation in the region’. Russia’s spokesperson, Maria Zakharova, denounced Norway’s official policy of deterrence and reassurance by claiming that Norway can no longer continue its ‘two-track approach’, where it, on the one hand, seeks cooperation with Russia in certain fields, but has a ‘destructive course’ on the containment of Russia, on the other. Russian foreign policy discourse suggests that Norway may have been misled by ‘external anti-Russian circles’, meaning first and foremost NATO and the US. It is suggested that the Norwegian security policy goes against the ‘true will’ of the Norwegian people.[7]

The non-allied status of Sweden and Finland has become increasingly important to Russia, to the extent that it criticises most forms of cooperation with NATO and the US. Russia suspects that joint exercises, increases in interoperability, and agreements between NATO and Sweden and Finland could eventually lead to membership of the Alliance. Russia has demonstrated its disapproval in practice, for instance by jamming GPS signals during NATO exercises in the High North.

Nordic defence cooperation is increasingly cast in a similarly negative light. For instance, when the Nordic defence ministers published a joint article about increasing Nordic defence cooperation in 2015, the Russia Foreign Ministry reacted negatively, claiming not only that the cooperation itself was directed against Russia, but also that such writing was promoting confrontational security thinking and introducing it to the wider public.[8]

Although the political goal is the same for Sweden and Finland, the policies aimed at influencing the decision on alignment are different towards the two countries. In the Swedish case, Russia has accused the Swedish authorities of Russophobic language and dangerous activities. In the case of its Finnish neighbour, Russia typically highlights the benefits of staying non-aligned and the importance of this for the wider security. Approaches aside, the bottom line is that the geopolitical frame is by far the most dominant one in Russia, and that the interpretation of good neighbourliness is becoming increasingly rigid with little security political leeway for all of the Nordic countries. Russia’s December 2021 proposals for “security guarantees” that would prohibit countries from joining NATO and limit US activities in Europe made explicit Russia’s desire to have a belt of buffer states around it, including in Northern Europe.

Geoeconomic levers

Russia has been a forerunner in forming a competitive geoeconomic strategy, openly mixing strategic and commercial goals for a long time. Economic interests do matter, but they are also seen as potential tools for the promotion of security-related goals. Furthermore, Russia’s primary exports such as gas and oil are highly strategic and often create long-term dependencies.

Despite its own geoeconomic ambitions, Russia frames business relations between itself and the Nordic states as purely ‘pragmatic’; if the issue of a political agenda or security interests behind the business deals is taken up by Nordic actors, Russian authorities often make reference to ‘Russophobic hysteria’ or ‘paranoia’ in their comments. For example, when Swedish newspaper Dagens industri published an interview with a Swedish researcher on industrial espionage and hostile hybrid influencing, the Russian foreign ministry commented on its website that the publication intentionally wanted to keep ‘Russophobic emotion in society at a high level’.[9] In a similar vein, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov also ridiculed a Norwegian journalist who dared to ask about espionage by claiming that he was ‘brainwashed with propaganda’. This discursive strategy of complete denial and ridicule is a traditional one that has been in active use through Soviet times up to the invasion of Crimea.[10] In a sense, this strategy plays with the earlier technocratic ‘gateway’ frame – but merely as a discursive construct.

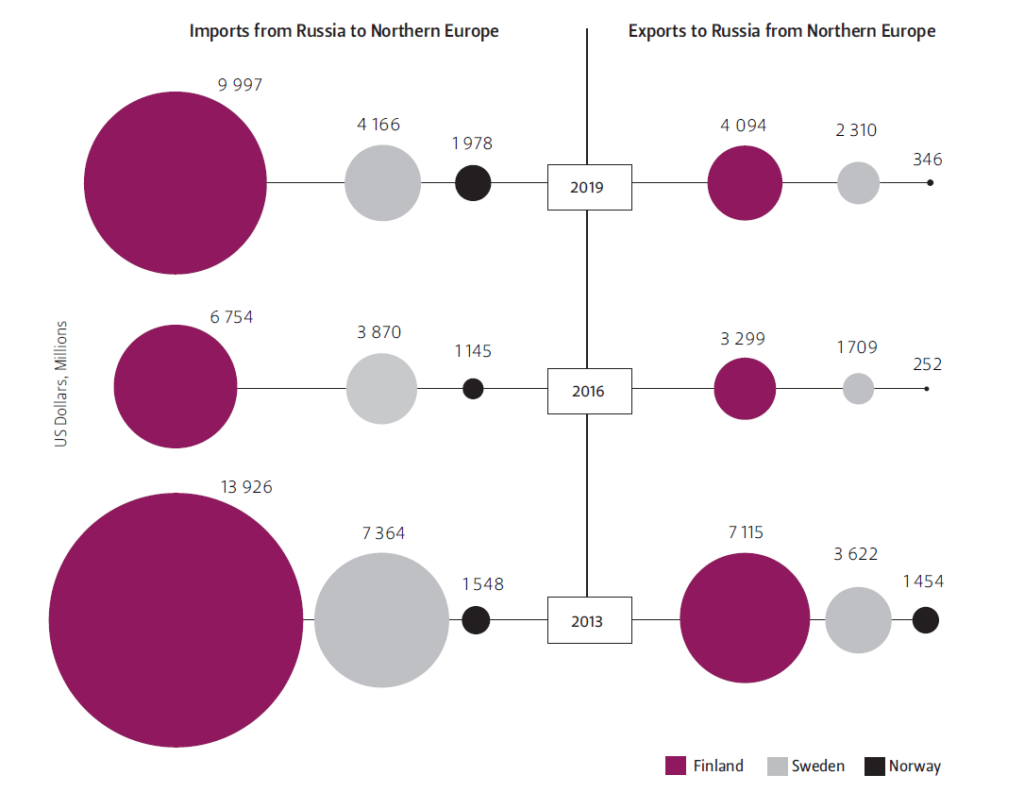

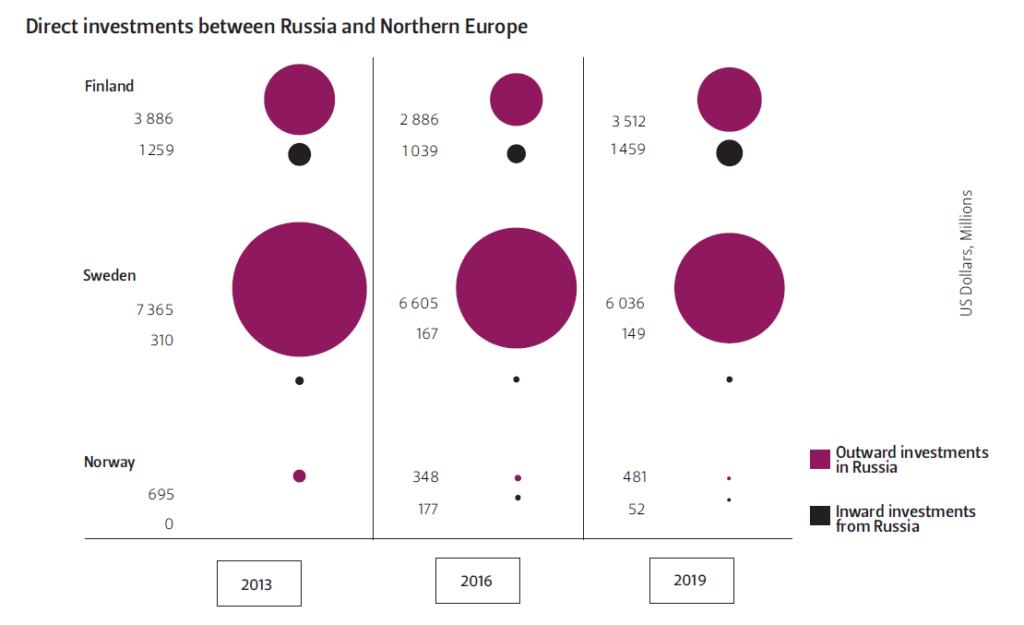

Figures 2 and 3 show the key numbers concerning Russia’s bilateral economic relations with Finland, Sweden and Norway. Finland is economically more dependent on Russia than other Nordic states, due to its much higher level of investment, economic cooperation and trade. For instance, in 2013 the United Shipbuilding Corporation, a Russian state-owned company, bought all the shares of Arctec Shipyard in Helsinki (which it had previously co-owned with Korean STX). After the EU sanctions against Russia made running the business increasingly difficult, the USC sold the company to two private Russian owners with close connections to the Kremlin; the chairman of the board is a former deputy minister. Furthermore – and even more importantly – through the Fennovoima nuclear power plant project and Rosatom’s significant share in it, the dependency will grow even if the general awareness of the risks linked to it has increased.[11]

Figure 2. Imports and exports between Russia and countries of Northern Europe.

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Figure 3. Direct investments between Russia and countries of Northern Europe.

N.B.: Norway’s investments in Russia go typically through the National Wealth Fund and are therefore not included in this figure (see page 9).

Source: Coordinated Direct Investment Survey (CDIS), IMF

Finland and Sweden buy oil from Russia, but Finland is the only Nordic state with significant dependency on Russian gas. In addition, Finland buys both uranium and coal from Russia. Rerouting purchases to other countries would be very costly, possibly also politically. Through the Finnish energy company Fortum’s ownership of German energy company Uniper, Finland also has a special interest in seeing Nord Stream 2 completed. Finnish dependency on Russian energy products is softer in the sense that the threat is not about Russia pressuring Finland by cutting deliveries, but more about fear of losing the economic benefits and favourable conditions that maintain Finnish global competitiveness.

Although Russia-Norway trade is not significant in volume, there is more to economic cooperation than meets the eye. The Norwegian direct investments in Russia (see Figure 3) appear low, but the figures only cover equities that grant 10 percent or more of the voting power in the enterprise. At the same time, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund continues to invest in Russian companies, and from 2018 to 2019 the value of these holdings increased by 1,3 billion US Dollars, totalling 3,6 billion US dollars at the end of the year. [12]

The countries also collaborate on the exploration of hydrocarbons and the management of resources such as fisheries and the Arctic sea routes. Moreover, the Russian companies Rosneft and Lukoil have been granted licences for exploration on the Norwegian continental shelf. Russia is greatly interested in the Arctic know-how that Norwegian firms possess. The Norwegian counter-intelligence service has reported that Russia is using espionage to glean petroleum and maritime industry secrets (alongside other actors such as China), and there have been arrests relating to these fields.[13] In 2021, Norway blocked a planned deal by Rolls-Royce to sell a maritime engine factory in Bergen to a Russian company on national security grounds. On the other hand, the Norwegian Wealth Fund has increased its ownership in Russian companies in the oil and gas sector.

All in all, the Nordic states were rather late in waking up to Russia’s geoeconomic influencing, but have clearly become more aware of, and prepared for, the risks in recent years.

Conclusion: frames vs. policies

As stated at the beginning of this paper, the developments in the Nordic region reflect the overall changes in Russian foreign policy. Although realpolitik was never completely absent, the policies in the 1990s put greater emphasis on cooperative relations and regional multilateral frameworks. Later, the focus shifted more towards economic collaboration with the Nordic states. Since Putin’s ‘third coming’ in 2012, there has been heavier emphasis on geopolitics and more open confrontation with the West.

Despite the geopolitical tensions, the collaboration between Russia, Norway, Finland and Sweden continues in a few important but restricted fields. For instance, cooperation in the field of emergency preparedness and environmental issues in the Barents and the Baltic Sea; and drills on oil-spill management, search and rescue and so on continue to take place without major disruptions. While this is important, the cooperation has not encouraged confidence-building and cooperation in other policy fields, such as security policy.

In a somewhat bizarre way, the pragmatic win-win policy frame popular in the early 2000s continues to thrive – but only as a discursive Russian strategy. Despite the fact that geopolitical and geoeconomic influencing is clearly spelled out in key Russian strategic documents, Russian diplomats often make fun of Nordic concerns; they promote the idea that Nordic states should base their small state policies on ‘pragmatic’ collaboration with Russia – meaning maximising profit and ignoring any security concerns by cooperating with Russian actors, acquiescing to Russia’s policies in Ukraine and elsewhere, and refraining from extensive security cooperation with major Western actors – and even from extensive Nordic defence cooperation.

Consequently, it has become increasingly hard for the Nordic states to fulfil Russia’s criteria for ‘good neighbourly relations’ in the realm of security policy; the room for manoeuvre has shrunk considerably for all of the Nordic states. However, ignoring one’s own national security cannot be the criteria for legitimate and just ‘good neighbourliness’.

Endnotes

[1] We freely borrow these frames from Katri Pynnöniemi, ‘Russia and the Nordic region: challenges and prospects for cooperation between the EU and Russia’, Fondation pour la reserche stratégique, Paris: December 2013. She refers to them in her paper as a “Place like no other”, a “Gateway” and “Geopolitics”.

[2]‘Russia With Stern Svalbard Warning to Norway’, High North News, 5 Feb 2020, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/russia-stern-svalbard-warning-norway; Konstantin Volkov, ‘Shpitsbergen polit potom i krov’yu nashikh predko’, Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 23 March 2020, https://rg.ru/2020/03/21/genkonsul-rf-na-shpicbergene-nelzia-delat-perekos-tolko-v-storonu-turizma.html.

[3] MFA of the Russian Federation, ‘Interv’yu direktora Vtorogo Yevropeyskogo departamenta MID Rossii S.S.Belyayeva mezhdunarodnomu informatsionnomu agentstvu “Rossiya segodnya”’, 18 November 2019, https://www.mid.ru/ru/maps/se/1476506/.

[4] President of Russia, ‘Telephone conversation with President of Finland Sauli Niinistö’, 14 December 2021, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67359.

[5] MFA of the Russian Federation, ‘Interv’yu Posla Rossii v Finliandii A.Iu. Rumiantseva informagenstvu “Rossiya segodnya”’, 10 February 2016, https://www.mid.ru/ru/maps/fi/1522383/.

[6] President of Russia, ‘Press statements and answers to journalists’ questions following Russian-Finnish talks’, 1 Jul 2016, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/52312.

[7] ‘Russian MFA: Oslo destabilizes the situation in the north’, The Barents Observer, 8 Aug 2020, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/security/2020/08/russian-mfa-oslo-destabilize-situation-north; ‘Moscow lashes out against Oslo, but courts Norwegian population’, The Barents Observer, 23 Nov 2020, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/security/2020/11/moscow-lashes-out-against-oslo-courts-norwegian-population.

[8] MFA Russia, ‘Kommentarii MID Rossii v svyazi so stat’ey ministrov stran Severnoy Evropy v Gazete «Aftenposten», 12 Apr 2015, https://www.mid.ru/ru/maps/no/1507167/.

[9] MFA Russia, ‘Ob ocherednom antirossiyskom vbrose v SMI Shvetsii’, https://www.mid.ru/ru/maps/se/1429040/.

[10] See e.g. Katri Pynnöniemi and Andras Racz, ‘Fog of Falsehood’, FIIA Report 45, 2016, https://www.fiia.fi/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/fiiareport45_fogoffalsehood.pdf.

[11] On the Helsinki Shipyard, see: Eero Mäkinen, ‘Helsingin telakka vahvassa vauhdissa’, Navigator magazine, 9 Jun 2021, https://navigatormagazine.fi/uutiset/helsingin-telakka-vahvassa-vauhdissa/; on the increased awareness of the risks connected with Fennovoima, see ‘Defence Ministry demands risk assessment of Fennovoima plant, cites ties with Russia’, Yle News, https://yle.fi/news/3-12157458.

[12] Norges Bank Investment Management, ‘Holdings as at 31.12.2019’, https://www.nbim.no/en/the-fund/investments/holdings-as-at-31.12.2019/.

[13] ‘Russian, Chinese intelligence targeting Norwegian oil secrets: report’, Dec 3 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-norway-oil-security-idUKKBN28D2M7; Jan M. Olsen, ‘Norway arrests citizen suspected of spying for Russia’, 17 Aug 2020, https://apnews.com/article/oslo-arrests-europe-denmark-norway-ce0fe8be7768cfdb06b89669c9e80e1f.