yhteenveto

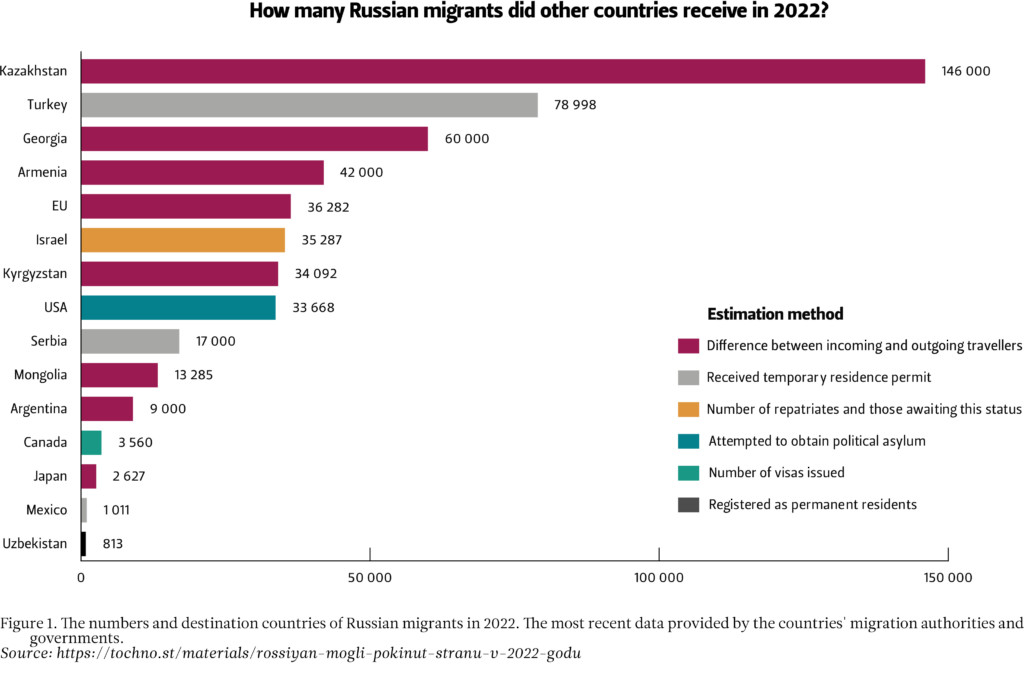

Noin 800 000 venäläistä on lähtenyt Venäjältä sen jälkeen, kun täysimittainen hyökkäyssota Ukrainassa alkoi 24. helmikuuta 2022. Suurin osa Venäjältä lähteneistä on päätynyt Kazakstaniin, Georgiaan, Turkkiin ja Armeniaan.

Sodan aiheuttamaan muuttoliikkeeseen tulisi suhtautua kuten mihin tahansa muuttoliikkeeseen, olipa sitten kyse turvapaikanhakijoista, taloudellisten syiden vuoksi muuttavista ihmisistä tai toiseen kotimaahansa palaajista.

Liiallinen politisointi ja pelon lietsonta maahanmuuttajilla, mukaan lukien poliittisista syistä pakenevat ihmiset, on haitallista, sillä se ruokkii Kremlin propagandaa ja sotanarratiiveja.

Vaikka vakoilun tai sabotaasin mahdollisuus herättääkin huolta vastaanottavissa maissa, huomion tulisi kohdistua ensisijaisesti venäläisten maahanmuuton sosioekonomisiin vaikutuksiin kohdemaissa. Erityisesti entisen Neuvostoliiton alueen maille venäläiset maahanmuuttajat ovat pikemminkin yhteiskunnallinen ja taloudellinen haaste kuin poliittinen uhka.

On todennäköistä, että Venäjä yhä useammin vainoaa tai sortaa poliittisista syistä lähteneitä kansalaisiaan ulkomailla. Sen vuoksi on tärkeää, että EU omaksuu johdonmukaisen suhtautumistavan poliittisiin maahanmuuttajiin – myös niihin, jotka tulevat Venäjältä.

Introduction

The war in Ukraine has produced the largest number of refugees in the European Union since the Second World War. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has also resulted in a large exodus of people from Russia, which poses tangible socio-economic and infrastructural challenges to receiving societies within the EU and beyond. While Russian emigration is significantly less numerous than the influx of those fleeing the war, its scale deserves additional scrutiny as it entails multiple implications for receiving countries.

Approximately 800,000 Russians have left their homeland so far due to the war in Ukraine, and in particular due to the ”partial military mobilization” announced on 21 September 2022.[1] Although the majority of EU member states continued to issue visas for Russian citizens, including for tourism purposes, several countries sealed their borders to Russian tourists after the announcement. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland banned leisure travel from Russia in early September 2022, and Finland joined them on 30 September. The political leadership of these countries insisted that travel is a privilege and not a human right. The major argument for denying Russians the right to cross the EU borders was ethical, pointing out that tourism during wartime is not appropriate. Yet other grounds mostly dealt with potential security threats, namely the likelihood of espionage, intelligence gathering, proliferation of potential saboteurs, as well as fears of Russian retaliation.[2]

Indeed, the influx of Russian migrants created tensions at the Georgian border and congested the Russian-Finnish border in late September. On the other hand, even before Russia’s western land borders were closed, the majority of migrants preferred the post-Soviet countries – Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Georgia – due to the visa-free entry and convenient transport connections. It is also worth mentioning that most Schengen tourist visas expired during the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition, people were aware of the high cost of living in Europe and of the fact that the mobilization in Russia could become a tipping point for some EU countries to begin to revise their migration regulations.

This Briefing Paper argues that the recent war-induced migration from Russia is unlikely to pose any major security threat to receiving states, although it has created challenges for them in terms of social security, real estate, and labour markets. The political impact on the receiving states has remained and will remain limited. The paper begins by considering the rhetoric of securitization around Russian migrants. It then discusses the attitudes and political behaviour of migrants in receiving states, concluding that seeing migrants as a potential source of change is more fruitful than excessive politicization of the issue.

A security risk or a driver of change in Russia?

According to the official statistics provided by receiving states, the number of war-induced Russian migrants that landed in the EU in 2022 is relatively small – 36,282 persons, while the post-Soviet countries and Turkey accepted an unprecedented number of incoming migrants. Most of the migrants ended up in Kazakhstan (146,000), Turkey (78,998), Georgia (60,000), and Armenia (42,000) (see Figure 1).[3] For example, the small state of Israel accommodated roughly the same number of Russian émigrés as the whole EU, and this figure does not even include those who were already in possession of Israeli passports but have only left Russia now.

According to a panel survey conducted by the OutRush research group in spring and autumn 2022, the choice of countries was mostly random and depended on airfare availability and entry regulations: 58% of the migrant respondents in spring 2022 confirmed that the choice of destination was random, 32% went to countries where their relatives or friends already lived, 13% were well acquainted with the culture of the receiving country, and 10% were relocated by their employer or went through programmes of international assistance (e.g., Scholars at Risk). For many, these countries turned out to be the final destination, but about a quarter continued their journey. According to the same survey, 56% stated that it is very likely that they will stay in their current countries.[4] That said, the EU states did not experience (and are unlikely to experience in the future) a dramatic surge in Russian migrants even before the visa bans and the border closures.

Yet Russian migrants became an overly politicized issue in certain EU member states. The potential security risks associated with Russian migrants are viewed as higher in the states that border Russia. For example, the Latvian Foreign Minister, Edgars Rinkevics, considered fleeing Russians to be a ”counterintelligence risk” as agents for potential covert operations could sneak in among them. His Estonian counterpart, Urmas Reinsalu, expressed similar concerns, referring to the Russian security service operatives who entered Ukraine on the eve of the annexation in 2014 and the full-scale invasion in 2022. He also claimed that ”many of the operatives of [the] Russian security services responsible for poisonings, explosions, et cetera, used tourist visas and false identities”.[5] There were even more radical statements of the kind that Russian émigrés could be instrumentalized and weaponized as a hybrid threat akin to the crisis at the Belarusian-Polish border in 2021. Historical traumas of Russian occupation have become re-politicized during the war and have also played a role in galvanizing the question of Russian minorities and Russian travellers during electoral campaigns in Estonia and Latvia.

A growing negative attitude towards Russia as an aggressor state had spillover effects on Russian speakers in general, irrespective of their political leanings, including those prosecuted by the Russian state. However, excessive politicization of incoming Russian migrants does more harm than good. Leisure travellers and political émigrés constitute different categories and must be treated differently. International humanitarian law protects persons who suffer threats from their governments or para-governmental organizations. Apart from those who face intimidation by the state, there are civil society activists, professional oppositionists, educators, and journalists who constitute the backbone of political resistance and thus bear disproportionate political risks compared to the rest of the Russian population. To preserve what remains of civil society infrastructure and networks in Russia, a more flexible approach by the EU and Finland towards Russian migrants would be more valid.

In February 2022, Dmitry Medvedev, Deputy Head of the Russian Security Council, referred to recent migrants who spoke out as ”traitors who have gone over to the enemy and want their Fatherland to perish”. In another social media post, he elaborated that ”in times of war there have always been special rules and quiet groups of impeccably inconspicuous people who effectively enforce them”.[6] Such messages clearly signal that crossing the Russian border does not mean being in a safe place. Cross-border or transnational repression – persecution or intimidation of political migrants abroad – has become a new challenge for Russians in exile. So far, Russian ex-territorial operations by the secret services have been limited to poisonings and mysterious deaths of certain businessmen abroad. Nevertheless, cross-border repression of political dissidents implemented by authoritarian states is not unheard of. No longer does President Putin refer to emigration as a de-toxification of Russian society; political migrants are seen as traitors, and therefore as objects of intimidation and prosecution. Thus, the danger is real and must be considered by the receiving states according to international humanitarian law.

So while it is unsurprising that precisely those EU member states that border Russia do not offer humanitarian visas and refuse to distinguish between regime opponents, economic migrants, and tourists, a more nuanced approach would be appropriate and is, in fact, overdue. In this context it is worth recalling that in August 2022, Finland’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Pekka Haavisto, announced an intention to grant humanitarian visas, although the procedure is still not available for applicants.

New Russian migrants in non-EU states

The nature of security threats for the post-Soviet countries differs from that faced by EU states or Turkey and stems from closer ties with Russia, weaker military capacity, as well as perceptions of historical legacy linked to Russia. For example, Georgia lost control over parts of its internationally recognized territory after Russia recognized the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. These circumstances give the government in Tbilisi additional incentives to hedge against new political risks. For instance, Georgia denies right of entry to some outspoken Russian oppositionists. Other post-Soviet states also pursue a risk-averse strategy in handling communications with the Kremlin while continuing to accommodate Russian draft evaders, IT specialists, and political opposition. So far, there are very few cases of extradition or denial of entry, but at the same time, the logic of political risk-aversion suggests that Russian oppositionists are not entirely safe in these states. All states tend to welcome economic Russian migration, but this does not mean that they offer opportunities for civic and political activism.

The nature of the political regimes in receiving countries does play a role in how a government reacts to the incoming migrants from Russia. One opinion poll found that as many as 69% of respondents in Georgia believe that Georgia should introduce a visa regime for Russian citizens, and 57% consider the Georgian authorities’ approach to the entry of Russian citizens unacceptable.[7] It cannot be ruled out that the Georgian political leadership may eventually be receptive to such demands, although President Salome Zourabichvili does not deem the Russian migrants – including draft evaders – a security threat. As authoritarian regimes, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan have the possibility to ignore public opinion, although it seems that the general perceptions of Russian migrants are more favourable compared to those encountered in Georgia. In Kazakhstan, the overall attitude is more positive, and the influx is viewed as a chance to promote Kazakhstan and capitalize on highly qualified labour.[8] President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s government also strives to downplay any tensions. However, following the example of the Georgian government, Kazakhstan did amend its rules of temporary residency: under the new rules, the period of stay in the country cannot be reset by leaving and immediately returning.[9]

Despite the tightening of migration legislation even in visa-free countries, Russian migrants have succeeded in creating civic networks and organizations in the receiving countries. They cover a variety of functions from private schooling and psychotherapy to civic education and political activism. The anti-war and anti-Putin political orientations serve as the basis of solidarity for the war-induced wave of migrants: more than 80% of migrant respondents in March–April 2022 knew and used the so-called ‘smart vote’ recommendations.[10] In comparison, only 12% of all Russian respondents in March–April 2022 were aware of the ‘smart vote’ and what it entails. Migrants do not trust the Russian government and less than 1% said they had voted for the United Russia party. Migrants are extremely active politically and willing to maintain horizontal networks. Interest in political life in Russia often goes hand in hand with a growing interest in their new country’s politics. More than half of the respondents were interested in the politics of the country where they found themselves at the time of the survey. Still, interest in the Russian political agenda does not necessarily translate into actual engagement in the politics of the host country.

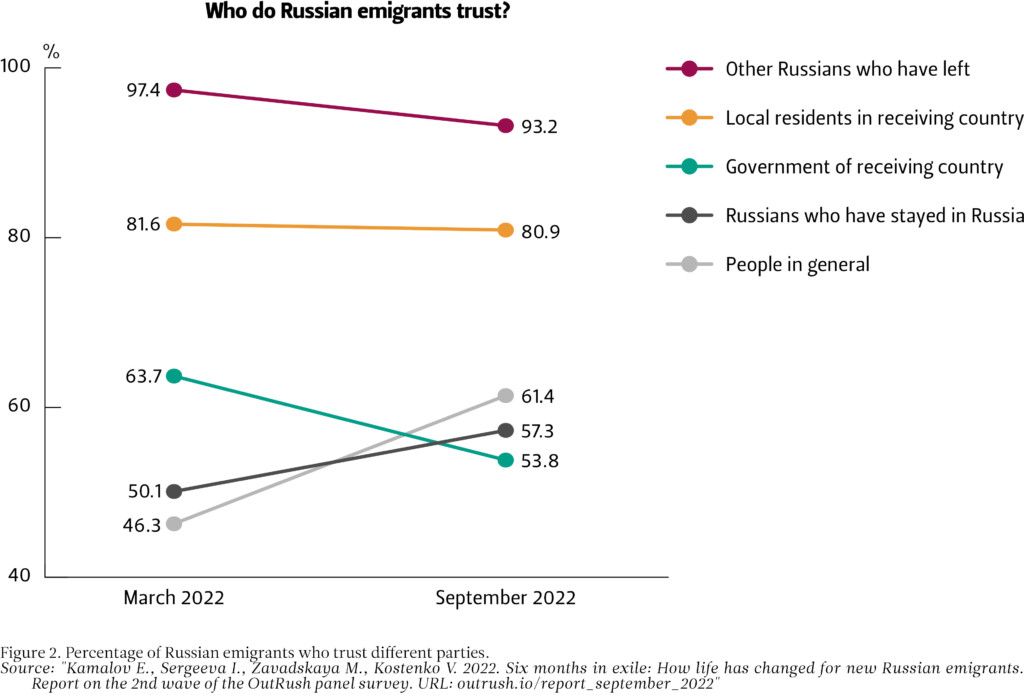

The data on trust dynamics among migrants clearly shows that the degree of trust in fellow émigrés is enormous and amounts to more than 90% (see Figure 2). Trust in receiving societies among Russian migrants also remains high (80–81%). Meanwhile, trust in the governments of receiving countries decreased by 10 percentage points from 63.7% to 53.8% from late March to late September 2022, indicating that the emigrants may have had negative experiences when dealing with migration authorities and, perhaps, difficulties with settling in.[11] The decrease can be attributed to difficulties in opening bank accounts, obtaining visas, and other problems faced by emigrants when dealing with state and financial institutions, as well as the lack of institutional assistance from the states. The migrants’ ‘rosier’ vision of the world outside Russia has undergone adjustments, although they still trust the societies that host them, are willing to learn the language, and express interest in the politics in their new home countries.

Economic challenge or potential asset?

The post-Soviet states receiving Russian migrants have largely faced challenges of an economic nature: real-estate prices have skyrocketed and unemployment rates have soared. For example, even in March 2022, the real-estate price per square metre in the centre of Yerevan had risen by 20%.[12] On the other hand, according to the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the economic forecasts for Armenia and Georgia were revised upwards.[13] A manifold increase in domestic spending and transfers from Russia stimulated economic growth.

Having said that, the financial situation of emigrants has deteriorated during the year. For every second middle-income respondent, it has become difficult not only to buy appliances but also clothes. Draft evaders are likely to be among the most economically vulnerable groups. Now migrants are transitioning from Russian employers to international and local companies, freelancing or starting a business. Predictably, economic ties with Russia are loosening. Hence, the inflation shock for the migrants is a one-off impact that will subside in the future as their economic well-being is likely to improve over time. At the same time, resourceful migrants are launching private schools and day-care centres, cafés, and open spaces, thereby creating parallel structures to those of the receiving states and in a certain way compensating for the lack of public goods provision. In other words, migrants are investing in local infrastructure and creating new workplaces.

Some sceptics argue that Russian migrants left due to the lack of economic prospects and not because they are against the war in Ukraine. Such moral accusations may serve to legitimize more restrictive migration policies. However, an indiscriminate ban on migrants facilitates repression towards less numerous political dissidents and activists, not to mention the fact that such policies send a signal that discrimination against economic migrants with Russian passports is acceptable. In the final analysis, however, the outflow of educated and wealthy individuals as well as professionals is damaging the Russian regime, which is significant for all those who hope to see positive changes in Russia and the emergence of a more predictable and reliable neighbour.

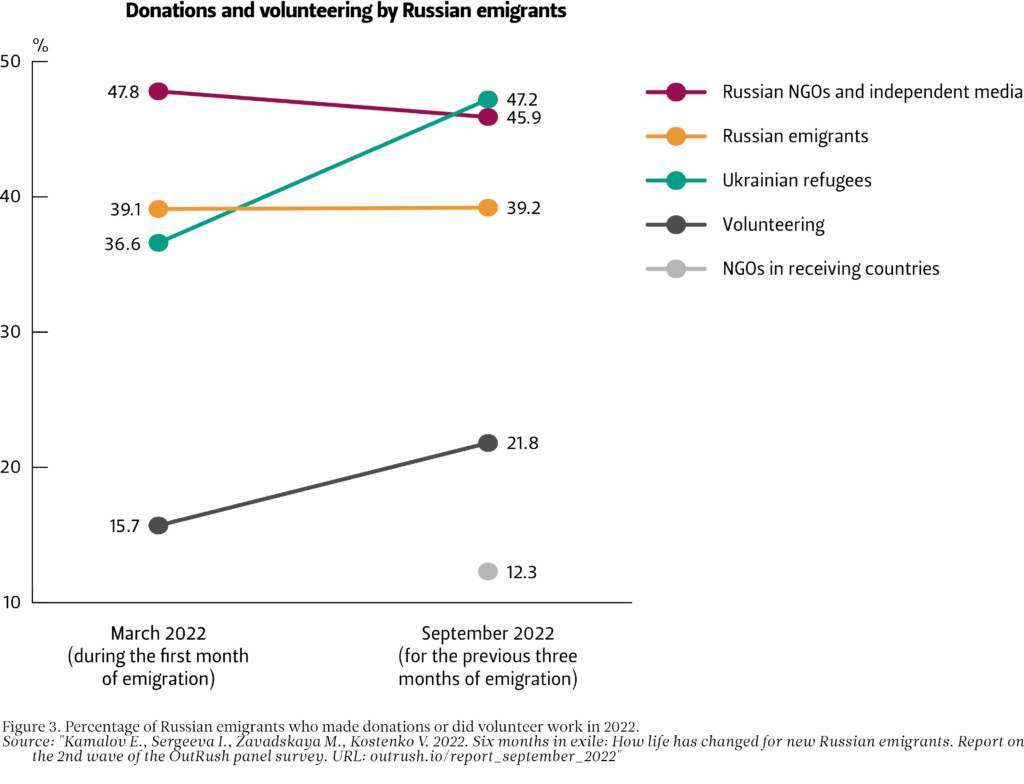

According to a panel survey, Russian war-induced migrants also engage in charity activities and volunteer work. Half of the emigrants donate to Russian independent NGOs and media such as Meduza (see Figure 3). There was a significant increase in volunteering, from 15.7% in March 2022 to almost 22% in the autumn. Russian migrants also actively support Ukrainian refugees through donations. The proportion of those who donate rose from 37% in the spring to 47% in the autumn. Finally, around 12% of surveyed migrants donate to local NGOs that are not related to the Russian diaspora.[14] These figures confirm that the war-induced wave of migrants do not support the Russian regime and share strong anti-war convictions.

Certain activities by Russian emigrants have been successfully institutionalized into transnational networks uniting hundreds of communities around the globe. After the full-scale war began, more than 128 peace organizations established by Russians abroad joined efforts.[15] Russian emigrants have also established organizations that aim to help Ukrainians, such as Russians for Ukraine in Poland. These organizations rely on the efforts of migrants and seek to establish contacts with fundraisers and authorities in receiving societies, thereby turning into advocacy organizations. One of the networks that aids Russians in moving and settling into new countries is Kovcheg (The Ark). The organization explicitly limits its assistance to those who share the anti-war stance and, in addition to legal and logistical assistance, organizes lectures and events of a political nature. The organization’s founder, Anastasia Burakova, has been labelled as a foreign agent in Russia. Another organization, Idite lesom (a play on words that means both ’escape through the forest’ and ’go to hell’), provides advice and offers safe routes to draft evaders, including professional military servicemen.

The political contours of Russian war-induced emigration gravitate around volunteering and civic education projects, while political organizations that would contest power inside Russia are admittedly less visible and their ties to civic organizations are weak. Yet this does not necessarily mean that these communities are ineffective in bringing about change in Russian domestic politics. Those who find themselves in democratic countries can gain practical skills and grow networks beyond Russian-speaking associations. They also maintain close ties with those in Russia and provide access to uncensored political information. Such organizations serve as external support for the Russian domestic opposition.

Conclusion

The exodus of Russians after 24 February 2022 has had a tangible socio-economic impact on receiving states, predominantly the countries of Central Asia, Georgia, and Turkey. The war-induced migration from Russia is unlikely to pose any major security threat to receiving states, and migrants should be seen as representing the potential for change instead.

Firstly, this wave of migrants differs dramatically from the average Russian citizens: they are more educated, wealthier, and share at least a strong anti-war and often also anti-Putin stance. Secondly, these people are politically active and continue to participate in civic initiatives in countries where they settle, even if these activities mostly target Russian society; importantly, they are not yet inclined to engage with host states’ domestic politics. Thirdly, escaping the Russian political and legal system allows these individuals to communicate freely without exercising excessive caution and self-censorship, as well as transmit alternative media narratives back to Russia in the same way that USSR dissidents were able to disseminate forbidden literature and news from abroad. Finally, politicization of the issue of Russian immigration and imposing indiscriminate restrictions on Russian migrants would feed the Russian propaganda machinery and send the wrong signal to the Russian political opposition that it has been left to its own devices.

Restrictions on migrants are often justified on security grounds, under the guise of fear of sabotage and espionage. Such narratives exaggerate the perceived risks of Russian immigration and lead to a failure to differentiate between political activists, economic migrants, and tourists. Russian political migrants are no different from any other political émigrés – Belarusian, Iranian, or Syrian – and should be dealt with in accordance with international humanitarian law.

The increased likelihood of cross-border repression calls for a more consistent response and policies toward political migrants. Offering humanitarian visas would be a flexible and less costly tool to provide political activists with access to proper protection. Asylum decisions should always be based on objective criteria and individual assessments. Understandably, war refugees must be the priority; however, support for Ukrainian war refugees and Russian political refugees must not be viewed as ’a zero-sum game’, where assisting one group rules out helping the other. The war in Ukraine will be over at some point, but Russia as a political entity is likely to remain in one form or another. Hence, the EU as well as its Eastern neighbours would be better off pursuing fine-tuned policies aimed at a longer-term perspective, as the new Russian political leadership may potentially emerge from the opposition in exile.

Endnotes

[1] Ширманова, Ирина (2023) 800 тысяч россиян могли покинуть страну в 2022 году. Tochno, 27 February 2023. https://tochno.st/materials/rossiyan-mogli-pokinut-stranu-v-2022-godu.

[2] Braw, Elisabeth (2023) “How Estonia is Planning for the Worst”. Foreign Policy, 7 March 2023. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/07/estonia-defense-planning-russia-ukraine-war/; Umarov, Temur (2022) “After Ukraine, Is Kazakhstan Next in the Kremlin’s Sights?” Carnegie Politika, 10 August 2022. https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/87652.

[3] Ebel, Francesca and Mary Ilyushina (2023) “Russians abandon wartime Russia in historic exodus”. The Washington Post, 13 February 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/02/13/russia-diaspora-war-ukraine/.

[4] Kamalov, Emil, Ivetta Sergeeva, Margarita Zavadskaya and Veronica Kostenko (2022) Big exodus: A portrait of new migrants from Russia. Report on the first wave of the online survey. OutRush, April 2022. https://outrush.io/report_mar022.

[5] Maghaldadze, Ekaterine (2022) “Russian Refugee Exodus Poses Dilemma for Its Neighbors”. VOA Europe, 28 October 2022. https://www.voanews.com/a/russian-refugee-exodus-poses-dilemma-for-its-neighbors-/6810261.html.

[6] Borogan, Irina and Andrei Soldatov (2023) “Kremlin Crosshairs Focus on Exiles”. CEPA, 13 January 2023. https://cepa.org/article/kremlin-crosshairs-focus-on-exiles/.

[7] NDI poll: 69% of respondents believe that Georgia should introduce a visa regime for Russian citizens, and 57% consider the Georgian authorities’ approach to the entry of Russian citizens unacceptable. Interpress News, 2 February 2023. https://www.interpressnews.ge/en/article/123669-ndi-poll-69-of-respondents-believe-that-georgia-should-introduce-a-visa-regime-for-russian-citizens-57-consider-the-georgian-authorities-approach-to-the-entry-of-russian-citizens-unacceptable/.

[8] Berdiqulov, Aziz (2022) “Russian Migrants in Central Asia – An ambiguous Reception”. ECMI Minority Blog, 25 July 2022. https://www.ecmi.de/infochannel/detail/ecmi-minorities-blog-russian-migrants-in-central-asia-an-ambiguous-reception.

[9] Feoktistova, Olga (2023) “Kazakhstan tightens visa rules for citizens of Russia, Armenia, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan”, Forum Daily, 17 January 2023. https://www.forumdaily.com/en/kazaxstan-uzhestochil-vizovye-pravila-dlya-grazhdan-rossii-armenii-belarusi-i-kirgizii/#.

[10] Political know-how by Alexei Navalny and the FBK that strengthens coordination of opposition voters around the second-best candidate running in single-member districts, thereby causing maximum electoral damage to United Russia.

[11] Kamalov, Emil, Ivetta Sergeeva, Margarita Zavadskaya and Veronica Kostenko (2022) Six months in emigration: How the life of Russian migrants has changed, OutRush, September 2022. https://outrush.io/report_september_2022.

[12] Avetisyan, Armine (2022) “Russian Migration Shakes Up Armenian Economy, Society”. The Moscow Times, 2 October 2022. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2022/10/02/russian-migration-shakes-up-armenian-economy-society-a78935.

[13] Gabritchidze, Nini (2022) Russian influx boosts Georgian economy, but not everyone is feeling the boom. Eurasianet, 17 November 2022. https://eurasianet.org/russian-influx-boosts-georgian-economy-but-not-everyone-is-feeling-the-boom.

[14] Kamalov, Emil, Ivetta Sergeeva, Margarita Zavadskaya and Veronica Kostenko (2022) Six months in emigration: How the life of new Russian emigrants has changed, OutRush, September 2022. https://outrush.io/report_september_2022.

[15] Карта мира. Русскоязычные антивоенные сообщества (Map of peace. Anti-war inititiaves by Russian speakers.) https://mapofpeace.org/