Summary

After the 2008 financial crisis, the EU’s approach towards China shifted from overconfidence in European normative power to an embrace of unconditional economic engagement with China.

The EU policy of de-risking is critically important, but it needs to be carefully considered, managed, and communicated to China.

US-China tensions and American debates on China impact the EU’s approach. Nevertheless, there are significant differences between European and US positions on China irrespective of which party holds power in the US.

China’s position on Russia’s war of aggression is a make-or-break issue for the EU. By actively enabling Russia’s invasion, China is harming its own long-term interests in Europe and globally.

It is in Europe’s interests to avoid framing current international dynamics in terms of “the West and the rest”. Although this discourse may be popular domestically, there is a danger of it becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Introduction

This autumn, the EU conducted its strategic discussion on EU-China relations and is now preparing for an end-of-the-year EU-China summit.[1] The EU discussion aims to review the Union’s 2019 formulation of China as simultaneously a ‘negotiation partner’, an ‘economic competitor’ and a ‘systemic rival’.

The strategic discussion highlighted two intertwined challenges. First, how to manage current political tensions in the bilateral relationship between China and the EU stemming from the securitization of geoeconomic dependencies. Second, how to navigate the wider geopolitical context and uncertainties related to it. This Briefing Paper aims to illuminate these challenges, their possible future trajectories, and their potential implications for EU-China relations.

The paper argues that there are no quick fixes for the China-EU tensions. China is and will remain a challenging partner: a huge, dynamic and authoritarian country increasingly intent on leaving its own mark on global governance, often in ways that diverge from the EU’s preferences. Despite this, the EU should refrain from a complete break with past policies and act prudently and systematically to advance its interests, while simultaneously avoiding over-securitizing the relationship. The EU needs to pursue its relationship with China while acknowledging the wider geopolitical context, which is marked by critical uncertainties. Given the dissonance in normative regimes and vastly different systems of governance and policymaking styles between the EU and China, mutual miscommunication and misunderstandings remain a formidable challenge.

Context: shifting EU-China dynamics

The EU’s relationship with China has always been a mirror of the prevailing zeitgeist. Immediately after the turn of the millennium, the EU was full of optimism about the future and believed in its own global transformative power. This overconfidence in the global attractiveness of European values was reflected by a commentator who professed in 2005 that India, Brazil, South Africa and China “will join with the EU in building a ‘New European Century’”.[2] Contrary to this assertion, China was not persuaded by European normative appeal – human rights issues and democratic norms have served instead as a source of mutual estrangement and distrust between China and the EU, while China has become internally more repressive and autocratic.

Estrangement gave way to deepening economic engagement in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008 and China’s phenomenal economic rise in the years that followed. Perceptions of a triumph of the ‘China model’ and of a major shift in power from the West to China began to dominate debates worldwide.[3] Many European states that were struggling with their sluggish economies were eager to develop closer ties with Chinese actors. In practice, the EU and its member states’ normative demands on China were also gradually diluted in the hope of fostering closer economic relations.[4] In 2010, China became the world’s second largest economy and its global prominence quickly grew under the new leader, Xi Jinping. In the 2010s, China launched the 16+1 framework in the EU’s Eastern member states and the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, which extended its influence over half the world. China also became a formidable player in international lending and FDI, and established a mushrooming network of Confucius institutes to enhance its global soft power.

Gradually, from around 2015, European perceptions of China started to shift again. European leaders and commentators called for greater reciprocity: Chinese investors benefitted from open European markets while European businesses lacked similar access to China. In many Western circles, China’s economic policies were seen as insincere and unfair, and distrust towards Chinese political intentions grew apace with China’s global assertiveness.[5] China’s increasing repression and stricter control over its citizens added to European distrust. In 2019, the EU adopted a strategic outlook on China, in which it referred to the country as simultaneously a ‘negotiation partner’, an ‘economic competitor’ and a ‘systemic rival’ for the EU.

The distance between China and the EU was further widened by the Covid-19 pandemic, which started in early 2020. The EU’s dependency on Chinese medical supplies and equipment, and unpreparedness for disruptions in production chains, caused growing criticism and insecurity. China’s policies did little to dispel these worries as it experimented with a more verbally aggressive discourse by some of its “wolf warrior” diplomats at the time.

However, the most dramatic shift came with Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine and China’s unwillingness to explicitly condemn the invasion. First, it increased awareness in the US and Europe of the conflict potential over Taiwan, as politicians and the media drew parallels between the two disputes. Second, the risks related to excessive dependencies on Russia materialized almost overnight, changing the way Europeans view economic risk related to China. Third, EU member states – the eastern ones in particular – became more likely to side with the US on tougher measures against China as a matter of alliance politics.

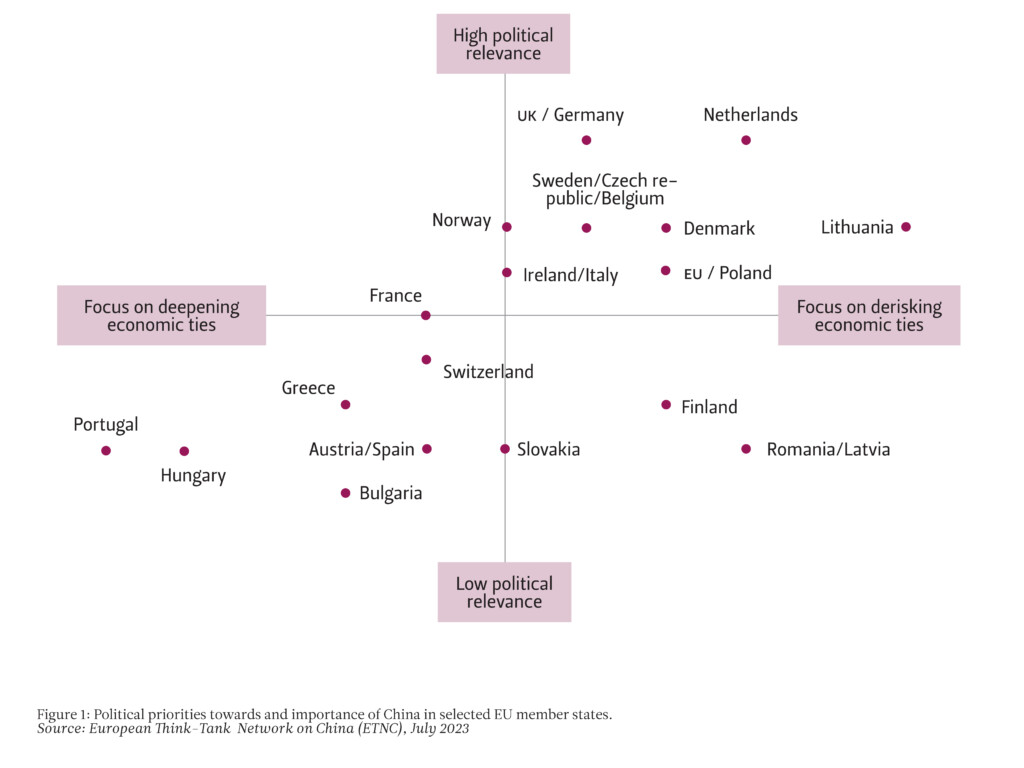

This is the setting for the EU’s strategic discussion process on EU-China relations with its member states. Strategic discussions and document updates are a typical way of making foreign policy within the EU. The institutions produce documents and policy incentives, yet member states often have room for manoeuvre in adopting and implementing them. While the EU strives to be a more coherent and assertive international actor, the Union’s external action continues to reflect the slow convergence of member states’ policies rather than the typical executive foreign policy of a great power. The EU member states remain undecided on how to approach China in this new setting. Some EU states see the world entering an era of confrontation between democratic and autocratic states and call for transatlantic unity against China and Russia. Others see a less confrontational and more multipolar future, where there is still room for deepening economic ties.[6] Between these two extreme positions, many variations exist (see Figure 1). The EU-wide trend is nevertheless towards a more cautious approach and economic de-risking.

Risks of de-risking

The Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine have taught the EU hard lessons about the dangers of asymmetric dependencies in critical industries. The EU-China economic relationship is more complex than that with Russia, given China’s leading role in global trade and manufacturing, the size of its market, and the FDI of European companies – especially from Germany, the Netherlands, France, and the UK, which accounted for 87% of European FDI in China on average between 2018 and 2021.[7] China has attained a central position in the global ICT, digital and green technology value chains, and has become an important source of the critical raw materials that drive the net-zero transition. With growing dependencies come new security concerns, and risks that need to be managed and mitigated. [8]

As spelled out in the latest EU economic security strategy from June 2023, the EU’s international economic engagement is focused on de-risking. Most of the proposed actions revolve around identifying risks in the EU’s economic partnerships, from foreign technology in critical infrastructure to supply chain risks and strategic technologies. A new focus of concern is European outbound investments, given the risks of industrial espionage and technology leakage.

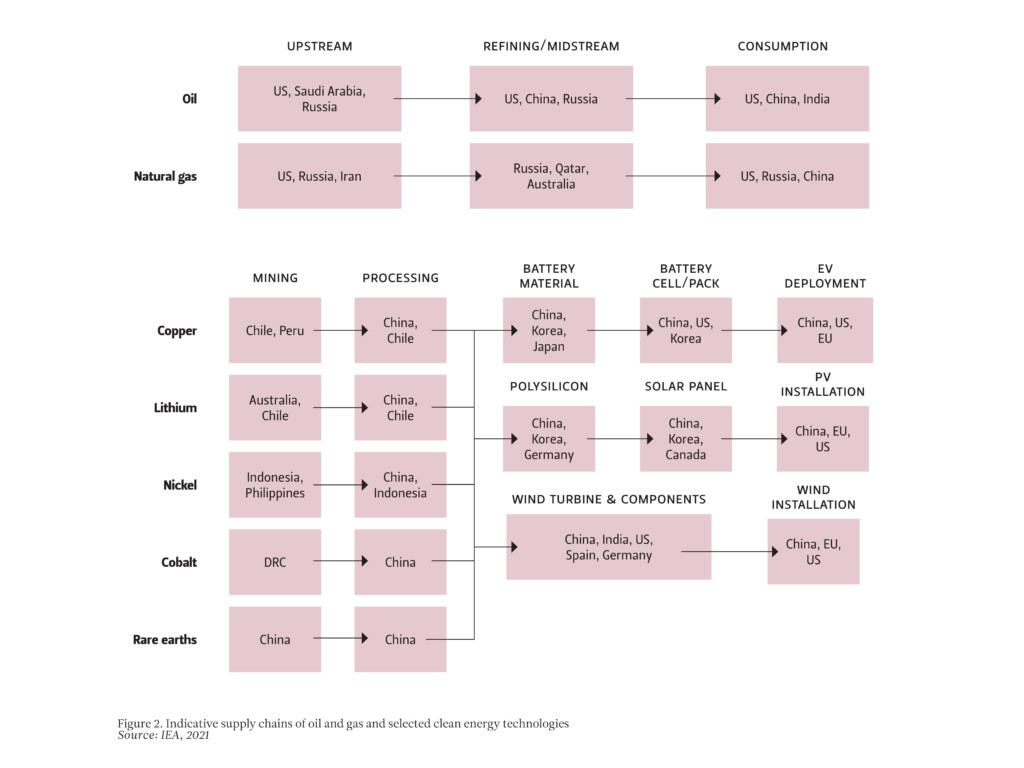

China’s economic role is essential for Europe’s green transition, which is a fundamental political priority for the Commission (see Figure 2). Currently, China accounts for 97% of wafer production for solar panels, produces three quarters of solar panels globally, manufactures 80% of components for wind turbines, and hosts 60% of global cobalt and lithium refining needed for battery technology.[9] Given the political importance of a smooth and not excessively expensive energy transition, it is only logical that the EU has become more alert to potential supply chain risks.

The EU has attempted to communicate to China that it is treated no differently from other states and that the EU’s measures are gradual and restricted to security-related fields. However, following China’s and the US’s respective policies of high tariffs and other trade barriers, there is also political pressure on the EU to adopt more protectionist measures.

In her State of the Union speech in September 2023, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced an EU investigation into China’s subsidies for its electric car industry to determine whether they give companies an unfair advantage in European markets. This measure is indicative not only of Europe’s growing fear of overreliance on China for materials and products needed for the EU’s green transition, but also of protecting key domestic green industries. The probe sparked fears of a looming trade war and the risk of Chinese countermeasures against European car manufacturers (mainly from Germany) that have invested heavily in the Chinese market.

Major questions remain regarding the feasibility of de-risking in the short and medium term, and how it should be carried out in the most efficient and affordable way for European businesses. Critically, the EU’s policy of de-risking needs to be carefully considered, managed and communicated. Otherwise, the EU might end up with a negative scenario in which misunderstandings and miscommunication lead to a vicious spiral, with China taking economic countermeasures against the EU. This in turn would again highlight the risks of economic dependency on China, pushing Europe from a limited de-risking agenda towards wider decoupling.

Furthermore, the EU’s de-risking agenda is highly dependent on the development of US-China relations. It is often presumed that if bipolar competition between the US and China intensifies and turns into more outright confrontation, the EU’s independence as a global actor and its room for manoeuvre with regard to China will diminish. However, the next section argues that this may not be the case.

Between a rock and a hard place: the US factor

US attention towards China and the possible security threat it may pose has been increasing since the late 2000s, when the Obama administration announced its ‘pivot to Asia’. The Trump administration accelerated this competitive discourse on China and increasingly framed it as an economic rival. [10] The Covid-19 pandemic contributed to a harsher political climate between the US and China, and by the time President Biden entered office in 2021, a tough line on China had become an issue of rare bipartisan consensus in Washington. Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine added to American concerns regarding China, as it supported pre-existing narratives that paint Ukrainian defence efforts as part of a larger conflict between democracy and authoritarianism.

Given the increased importance of the transatlantic security and defence alliance for EU member states, US positions and policies are and will be a crucial factor in the EU’s approach towards China. The volatility of US internal politics increases uncertainties concerning the future of US-China relations, and indirectly of EU-China relations as well.

However, there are fundamental differences between how the EU sees China and how the US, as the dominant great power, views its rival. Overall, the US is much less willing to permit any strengthening of China’s influence globally, whereas the EU is more concerned about the type of global influence that China wields. The US sees the emerging world order in terms of bipolar competition, whereas China and the EU both assume a shift towards a more multipolar world, albeit with different perspectives. While China sees multipolarity as a vehicle for ending the prevailing unfair US-led Western dominance, the EU favours multilateralism to defend and strengthen the liberal rules-based order and thus its own power and standing in world politics.

A second term for the Biden administration could strengthen more responsible US foreign policy and a more economically sound de-risking strategy towards China. In his second term, President Biden could, at least to an extent, ignore some of the domestic pressure. A series of high-level delegation visits from the US to China – Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and Commerce Secretary Gina Raymondo – bore witness to a strategy of cautious de-escalation in 2023. Such diplomatic efforts could grow into something resembling a political thaw, which would allow the EU to have stronger independent agency in its relations with China.

In contrast, a new Republican administration and continued aggressive political rhetoric around China might lead to more reckless foreign policy choices and a deepening rift between the great powers. In this case, heightened confrontation between China and the US is not likely to bring about transatlantic unity. Instead, a second Trump administration would likely see the EU distancing itself from Washington. Should Washington attempt to negotiate with Moscow without the backing of Ukraine and Europe, or escalate tensions concerning Taiwan, European capitals would seek strategic autonomy even more determinedly.

There are some factors that would undoubtedly push the EU to side with the US positions more strongly. The first potential scenario is if China were to use overwhelming military force against Taiwan (which the authors of this paper consider unlikely under the current conditions). The other potential scenario is if China were to start supporting Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine more directly.

Make-or-break issue: China’s stance on Russia’s war

During Xi Jinping’s time in power, Russia and China have both emphasized their mutual partnership. There is active public debate about the true nature of the China-Russia relationship, with some observers stressing its transactional nature and economic basis. Others see it as a deeper and more united “alliance of autocracies” to challenge the West on all fronts. As is often the case, the truth is likely to be found somewhere in the middle.

While both states see themselves as great powers and value their sovereignty of action, there is also a limited normative core consisting of a shared conviction that today’s world is unfairly dominated by the US and Western values. The partnership is also strengthened by the shared belief that the United States is hostile towards both regimes and would like to change the status quo in their countries. They have a shared incentive to support and legitimize each other’s autocratic regimes. [11] These fears, along with Russia’s rapidly deepening economic dependency on China, are the glue that holds together a partnership that would otherwise be fraught with diverging interests.

China’s hesitation and ambiguity in condemning Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has reshaped European perceptions of China and weakened its standing and influence within the EU. At the beginning of the war, China’s leadership probably believed that it could maintain a neutral position, effectively favourable to Russia, and benefit economically while continuing “business as usual” with the EU. Chinese leaders failed to realize that unlike the Crimean annexation of 2014, this time the Russian invasion was perceived as an existential threat in many European countries. Even tacit political support for Russia increased suspicions concerning China’s posture and its intentions towards Taiwan.

Russia’s decision to launch the war and its irresponsible nuclear threats and manoeuvres have likely eroded trust between China and Russia. Nevertheless, China has refrained from public criticism of Russia’s decision to wage war, and has supported its economic and, indirectly, military resilience by importing energy from Russia and exporting high-technology products and semi-conductors to Russia.

China has also continued to back Russian accusations of NATO’s aggressive enlargement policy and posture against Russia and abstained – along with over 30 other states – from voting on UN resolutions on Russia’s war.[12] Although China has rhetorically supported Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, it has also said Russia’s “legitimate security interests” should be respected, which in practical terms delimits Ukraine’s sovereignty.

In principle, the EU is willing to see China play a more active role in the negotiations to end the war in Ukraine, but in practice it expects unequivocal support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Contrary to the EU’s and Ukraine’s positions, China’s vision for peace most likely includes an “off-ramp” for Putin’s regime as well as limitations on future NATO enlargement.

The mismatch of principled positions does not exclude EU cooperation with China on more limited practical issues mitigating the horrors of the war. These smaller, concrete steps are what the EU should be actively promoting with China. Diplomatic efforts are also required to convince China that the renewed EU enlargement process is the best and most efficient way to stabilize the continent.

China’s support for Russia currently looks unlikely to weaken considerably, but this should not be completely ruled out. Should negative economic development in China raise the stakes of maintaining support for Russia, or should the war continue and turn even more violent and internationally disruptive, China’s support could gradually weaken or become more conditional. The EU should do all it can to convince China that this is the most responsible and constructive position China can take, even if such efforts might have limited impact.

It is also entirely plausible that China could further increase its assistance to Russia, for instance to ensure regime survival in Russia. No matter how unpleasant a prolonged major war might be for China, it does not want to see a regime change in Russia or Russia’s international standing severely weakened. Such a decision from China would be disastrous for EU-China relations and their economic cooperation, and would undoubtedly push the US and the EU closer together and further away from China.

For the EU, China’s position towards Russia’s war of aggression is a make-or-break issue. The EU needs to communicate this point to China clearly and repeatedly. By actively enabling Russia and conducting military exercises with Russia, China is harming its own long-term interests in Europe and globally. The EU’s enhanced ability to act more independently in international affairs could be a stabilizing factor in global affairs. This would also improve its ability to set the parameters of its relationship with China more independently.

Looking ahead

This paper has sought to highlight some of the key challenges affecting EU-China relations and to evaluate these challenges and their potential future trajectories realistically. It has argued that although the EU is a part of the ‘West’, there are key differences between US and European approaches towards China.

Even in cases where Chinese and European interests seem to partially overlap, engagement is often fraught. A case in point is the notion of reinforcing multipolarity in global affairs. Although this is a partly overlapping interest between China and the EU, their approaches and interpretations of what it denotes in practice are very different. The idea of a more democratic multilateral world order may be appealing for many European actors, yet the practical consequences of that may be harder for the EU to accept. Nevertheless, it is in Europe’s interests to avoid framing current international dynamics in terms of authoritarian countries vs. democracies. A more inclusive approach serves the EU’s long-term interests better.

As it pursues its much-needed de-risking agenda, the EU is walking a tightrope. Every step must be balanced very carefully. Otherwise, as this paper has argued, the EU might end up with a negative scenario in which misunderstandings and miscommunication lead to a vicious spiral where China takes economic countermeasures against the EU. This would jeopardize the EU’s other strategic priorities, such as the European Green Deal.

One of the most critical external drivers of EU-China relations is China’s indirect support for Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine. The EU needs to engage with China on Ukraine from a realistic standpoint, acknowledging the fundamental differences in approaches towards the war and its resolution. This does not, however, exclude cooperation with China on practical issues limiting the devastating effects of the war. The best ways to create confidence in EU-China relations are a realistic acknowledgement of the differences between the two sides, clear communication on EU positions, and honest dialogue on mutual fears and challenges.

Endnotes

[1] Borrell, Josep (2023) “EU-China relations: A candid exchange on our differences”. EEAS, 20 October, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-china-relations-candid-exchange-our-differences_en.

[2] Leonard, Mark (2005) Why Europe will run the 21st Century. Fourth Estate, London and New York.

[3] Breslin, Shaun (2011) “The ‘China model’ and the global crisis: from Friedrich List to a Chinese mode of governance?” International Affairs, vol. 87, No. 6. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41306993.

[4] Mattlin, Mikael (2012) “Dead on arrival: Normative EU policy towards China”. Asia Europe Journal, 10, 181–198, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10308-012-0321-7.

[5] Forchielli, Elena (2015) “Chinese Investment in the EU: A Challenge to Europe’s Economic Security”. 1 Jan, Paper Series of The German Marshall Fund of the United States, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep18744.

[6] Kratz, Agatha et al. (2022) “The Chosen Few: A Fresh Look at European FDI in China”. Rhodium Group,

14 September, https://rhg.com/research/the-chosen-few/.

[7] Mattlin, Mikael et al. (2023) “Enhancing Small State Preparedness: Risks of Foreign Ownership, Supply Disruptions and Technological Dependencies”, FIIA Report 74, https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/enhancing-small-state-preparedness.

[8] Kratz, Agatha et al. (2022) “Circuit Breakers: Securing Europe’s Green Energy Supply Chains”. ECFR Policy Brief, May, https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Circuit-breakers-Securing-Europes-green-energy-supply-chains_Kratz_Oertel_Vest.pdf.

[9] Gaens, Bart & Ville Sinkkonen (2020) “Great-power competition and the rising US-China rivalry: Towards a new normal?”, FIIA Report 66, September, https://www.fiia.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/report66_great-power-competition_rising-us-china-rivalry_web.pdf.

[10] Bartsch, Bernhard & Claudia Wessling (eds.) (2023) “From a China Strategy to No strategy at All”. The European Think-tank Network on China, July, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/ETNC_Report_2023_final.pdf.

[11] Ekman, Alice, Sinikukka Saari, Stanislav Secrieru (2020) “Stand by me! The Sino-Russian Normative Partnership in Action”, EUISS Brief 18, August.

[12] UN News (2023) “UN General Assembly calls for immediate end to war in Ukraine”, 23 February, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/02/1133847.