Summary

The conflicts in Syria, Libya and Iraq have spread instability and insecurity in the EU’s southern neighbourhood, and increased the number of migrants attempting to make their way to Europe with dramatic consequences at sea.

As a consequence, the EU has responded to the increasing migration pressures by attempting to control migration by increasing sea patrols and also by reviewing its neighbourhood policy.

The EU’s neighbourhood policy (ENP) is dominated by an agenda aimed at controlling migration towards Europe, which was not the original purpose of the policy. Europe’s Southern Mediterranean partners, unwilling to police the migration efforts, have requested the EU to increase the means for legal migration.

Currently, the EU is preoccupied with plans to launch military operations targeting traffickers, to further increase patrols and to share the burden originating from the southern migration more equally among the member states.

Relatedly, the ENP seems to be fading away, much like the general policy framework for the EU response to the developments in its southern neighbourhood, as the envisaged EU action is largely taking place outside of it.

Whether within or outside the ENP, the EU needs to improve its response to its Southern Mediterranean partners’ interests and priorities in order to maintain the special relationship with them.

Introduction

The Arab uprisings constituted a major turning point for most of the countries in the EU’s southern neighbourhood as well as for the EU itself, which had to respond to these developments. During the uprisings, people demanded freedom, basic human rights and better prospects for the future. Five years on, the democratic aspirations embedded in the uprisings have largely been replaced by fears of growing instability and insecurity in the region. Only in Tunisia has the ensuing transition led to some positive developments, although the situation is still fragile. Egypt is again under military control, and the violence continues in Syria and Libya.

The rise of ISIL/Daesh is another destabilizing factor which the EU is facing in its neighbourhood. The worsened security outlook for the broader region has led to significant migration flows to neighbouring countries and the EU. Thousands of people are trying to reach Europe at any cost and the EU is ineffectual in preventing risky trafficking by unsafe vessels, resulting in the loss of lives at sea. These are just a few of the consequences of the Arab Spring, clearly indicating that the EU policies, since the popular uprisings began, were neither sufficient nor effective. The EU’s neighbourhood policy was primarily intended to serve as an instrument to accelerate economic cooperation between the EU and its neighbours, but it was also applied as a response to the Arab Spring.

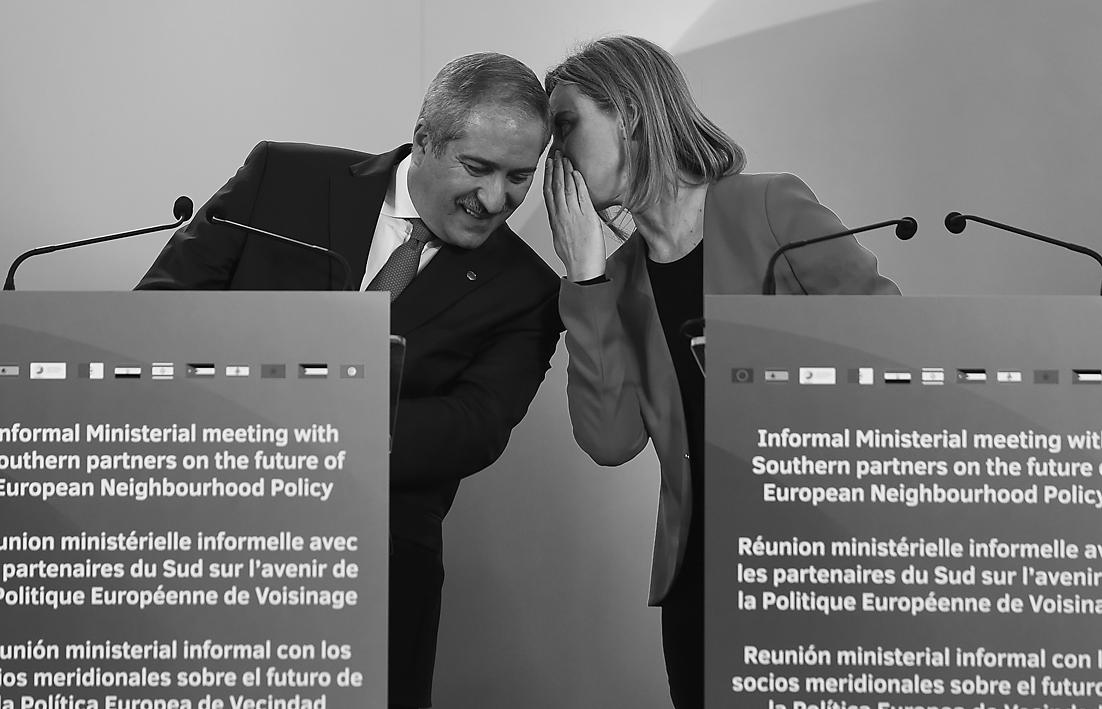

It is against this backdrop that the EU is currently reviewing its Neighbourhood Policy (ENP). This process aims to consult as widely as possible both with partners in the neighbouring countries and with stakeholders across the EU, in order to frame the future direction of the ENP.1 The earlier attempt to streamline the ENP in 2011 to better respond to the ongoing developments, including migration, has had limited results. The developments in the region have underlined challenges related to the ENP, which was initially designed to create stability by accelerating economic cooperation between the EU and its neighbours. However, restricting illegal migration is far from these original aims, which also included advancing “people-to-people” contacts between the EU its Southern Partner countries.2

Additionally, yet outside of the ENP context, the Commission has proposed immediate and mid-term measures to tackle the crisis situation in the Mediterranean by increasing patrols, internal burden sharing, and by suggesting that member states should consider CSDP operations in order to dismantle traffickers’ networks and to combat the smuggling of people.3 Based on the frustration related to the ENP on both sides of the Mediterranean, this paper asks to what extent migration, which is a deeply political question and firmly in the hands of the EU member states, can be tackled within the ENP framework.

The paper will first discuss the ENP as a response to developments in the EU’s southern neighbourhood in general, and then analyse the key ENP instruments utilised to address the migration challenges that have emerged.

Today’s challenges under the EU’s Neighbourhood Policy

The European Neighbourhood Policy4, designed in 2003 to develop closer economic relations between the EU and its neighbours,5 was based on the idea that growing prosperity would progressively improve political and institutional conditions in the EU’s neighbourhood, and the benefits would be mutual. However, over the past ten years, the significant political developments and crises that have taken place in the southern neighbourhood have shaken the belief that economic prosperity will lead to political stability, and have therefore challenged the usefulness of the ENP as such.

The first attempt to revise the EU’s Neighbourhood Policy was conducted swiftly in 2011 in response to the Arab Spring. The revision suggested increasing flexibility and tailoring responses in dealing with the rapidly evolving reform needs of the southern partners, but it failed.6 Some partners were actively seeking closer integration with the EU and others were not. Moreover, the transition paths of post-revolutionary countries in the region, such as Egypt, Libya and Tunisia, have varied due to pre-existing differences in their economic, political and social structures, as well as policies which the ENP review was not able to address.7

Although the concept of differentiation was reinforced in the 2011 ENP review, individual partner countries did not always find that their specific aspirations were reflected adequately. The lack of a sense of shared ownership with partners was seen as preventing the policy from achieving its full potential. These are just some of the examples expressed, not only by the southern partners, but also listed as questions that should be discussed in the EU’s ongoing ENP consultation, which for the time being is collecting experiences from the past five years in order to find a new direction for the ENP framework.

Today, however, five years later, as reflected also in the ongoing ENP consultation document, the question of security is dominating all the responses under the ENP framework. The growing level of instability in many countries in the EU’s southern neighbourhood has not only disrupted progress towards democracy but also threatened the rule of law, and violated human rights. Interestingly, the security sector reform did not play a major role in the ENP framework although it has been a key foreign policy tool for the EU since 2003. Effective security sector reform would be a fundamental step for countries undergoing (or attempting) democratic transition as it simultaneously aims to provide a security system that is capable of responding to internal and external threats.8

This lack of enthusiasm can partly be explained by the complex and dysfunctional legacy in the Arab World, where governments or security sectors have generally not been accountable to the people and where the people have been subjected to security, rather than the recipients of it. This applies in particular to Egypt, Algeria and Lebanon.9 From the EU’s perspective, security was principally understood as a tool aimed at controlling and steering migration towards Europe. Hence state-building efforts, which are mostly used under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) instruments, were not regarded as high priorities for the ENP, particularly as they do not link directly to migration.

Towards more tailored partnerships: Partnership for democracy and shared prosperity

The first main political instrument which was developed in 2011 under the renewed general framework of the ENP as a response to the Arab uprising was the so-called “Partnership for Democracy and Shared Prosperity”. A key objective was to support democratic transformations by increasing the role of civil society. For instance, in the case of Tunisia, the EU provided in excess of €400 million towards civil society capacity for 2011–13. This support included fostering dialogue, and organising international joint events, workshops and conferences together with other civil society actors locally and internationally, all of which were considered successful. The EU support was aimed at building civil society capacities in all kinds of sectors, ranging from archaeology to justice, security, media and women’s empowerment.10

Other methods under the Partnership to increase the participation of ordinary people included offering enhanced opportunities for exchanges and people-to-people contacts, with an explicit focus on young people. For instance, the “Erasmus Mundus” cooperation with universities for scholarships and exchange programmes was established. In 2014, the Youth in Action Programme drew over 300 young people for student exchanges, with the aim of promoting mobility among young professionals through internships on both sides of the Mediterranean Sea.

However, all the grassroots-level action took place rather slowly as the EU hesitated over who it should support. The EU institutions had not established contact with the civil societies in the Southern Mediterranean partner countries because they had neglected to maintain contact with representatives of political Islam during the decades of authoritarian rule. As many of these regimes changed, EU representatives found themselves unacquainted with the new political actors, as many of them originated from Islamist groupings. Owing to the hesitation on the part of the EU, time was lost at the beginning of the transformation, when people’s hopes were at their highest.11

Nevertheless, this new approach represented a fundamental change in the EU’s relationship with its partners by highlighting an incentive-based approach based on the idea of greater differentiation starting from the “people”. It was built on notions of conditionality and flexibility: those countries that progressed further and faster with their reforms would receive greater benefits from the EU.

Despite some positive steps, this partnership was criticised by the southern partners for three reasons: firstly, for ignoring the fundamentally different political dynamics in the south; secondly, for the feasibility of its conditionality; and thirdly, for the way in which it contradicted the principle of “joint ownership”.12 Above all, the question of differentiation was raised: Is there such a thing as a “neighbourhood” today in the sense of a natural grouping of countries to which it makes sense to offer common partnerships, especially at a time marked by ever-growing diversification?

On the other hand, the partners weren’t without their faults either. For instance, in the case of Tunisia, which has been the most successful ENP partner,13 the transformative changes have been beset by the hardship of economic recession and macro-economic instability, and by the government’s limited capacity to respond to specific expectations. Additionally, secular and religious divisions are re-emerging as Tunisia endeavours to determine the degree to which the role of the religious or secular identities of Tunisians will shape the state’s future. Since the Arab Spring began, debate and associated fears over the separation of religion and state are increasingly visible and divisive in Tunisia.14

The focus turns to migration

Security aspects linked to the question of migration were a dominant feature of the 2011 ENP review. The review clearly stated that some sections of the EU’s external borders are particularly vulnerable, notably in the Southern Mediterranean.15 Migration is the issue where the views of the EU and its southern partners diverge the most. Since the introduction of the ENP policies, increasing the means of legal migration to the EU has been the key goal for the EU’s southern partners. For them, options for legal migration to the EU are seen as the other side of the coin, namely the answer to the problems originating from illegal migration. According to the southern partners, the EU needs to strike a balance between facilitating legal migration and preventing illegal migration. This desire, as expressed by the southern partners, is not well reflected in the practical terms of the EU’s action.16

The growing security threat posed by migration was apparent immediately after the uprising began in the Southern Mediterranean neighbourhood. The EU Commission swiftly introduced a Communication on Migration in the wider context of the ENP in 2011,17 which has been updated regularly since then. One of the great weaknesses of this Communication, apart from the fact that migration policies do not fit into the ENP framework very well, is that the European legal and policy framework on migration is based on the sharp distinction between voluntary migration versus forced migration. At the practical level, migration is driven by a combination of motivations and factors which are far more complicated than that, and which should be addressed differently depending on the situation.

Perhaps to satisfy the southern partners, the Communication nevertheless spoke about the importance of remembering the human dimension in migration. It also emphasized that the means for legal migration should not be overridden by the need to control illegal migration and combat terrorism. This concern was also expressed by the European Parliament in a resolution in 2011 whereby the Parliament expressed its empathy towards giving migrants’ skills and educational levels adequate recognition.18

This migration-centred Communication painted a picture of a dynamic mobility policy comprising visas and liberalised provision of services, enhanced student and researcher exchanges, and intensified contacts, bringing civil society, business people and journalists together in order to achieve the goals set by the ENP, but without any specific measures on how to reach these goals. The Communication also failed to reflect reality as certain economic activities, such as agriculture in some southern European countries, are already based on the influx of cheap labour, mainly from Northern Africa.

Since 2011, the only precise measures have been those where the focus has been on tackling illegal immigration and terrorism. These have been swiftly implemented, while those highlighting the urgent need for providing means for legal migration are still, for the most part, awaiting implementation. This imbalance has been noted by the southern neighbours, who support preventing illegal migration and other security cooperation, but only as part of a package that also includes provisions for accelerating legal migration.

Currently, the fear of terrorism, political Islam, smuggling and organised crime, illegal migration and the wider spill-over effects of instability (particularly from Libya and Syria) have provoked many Europeans at national levels to oppose any unified attempts to increase legal means of migration to the EU. Many EU governments have called for increasing patrols, while the proposed planning of military operations in Libya to target the trafficking networks has also found some support in EU capitals. This course of action, however, will not solve the problem of migration flows to Europe, nor address the reasons underlying them.

Towards more flexibility: Dialogue on migration, mobility and security

A structured dialogue on migration, mobility and security in relation to the Southern Mediterranean countries was another concrete migration-related measure in the context of reviewing the ENP in 2011.19 To date, the EU has finalised dialogues with Morocco, Tunisia and Jordan. These dialogues allowed the EU to conclude mobility partnerships with Morocco in 2013, and with Tunisia and Jordan in 2014.

The implementation of the mobility partnerships included, for example, opening negotiations on an agreement for facilitating the issuing of Schengen visas for certain groups of people, particularly students, researchers and business professionals. However, sufficient safeguards were the condition for lifting mobility restrictions to work, which have not taken place so far. Further, the partners were asked to ensure that they would take every possible measure to prevent irregular migration and, to this end, agreed to conclude a re-admission agreement allowing for the return of citizens who do not have the right to stay in Europe.20

The logic of this dialogue was that the southern partners firstly need to provide satisfactory results in managing migration flows, and only when the situation is under control will the EU improve legal means for migration. Again, the main focus of the dialogue was on short-term measures to improve the capacities of the southern partners to manage migration flows in the Mediterranean with precisely listed action plans to secure the southern water border of the EU.

The dialogue only referred to aims to address the root cause of migration at the structural level, without answering questions such as how, when and by whom these objectives are going to be defined. In particular, the root cause of migration should have been clarified and touched on more specifically. This means that the current framework of the ENP, which covers 16 neighbouring countries, cannot be adequately addressed without taking into account, or in some cases cooperating with, the neighbours’ neighbours. The dialogue also left certain questions unanswered, such as how to deal with migration flows that destabilise the partner country, originate from a neighbouring country, or are caused by a civil war.

The EU’s lack of interest in increasing legal migration and mobility options can be explained by the fact that the migration issue is constructed in the security context, which is based more on fears than economic factors.21 Statistics show that Europe needs to import labour from the Southern Mediterranean due to the aging populations in European countries, but this factor is often overlooked in the securitized discussion on migration. Further, in many places in Europe, a growing part of the unskilled labour market is being dominated by immigrant workers, which is also overlooked in EU policies. Migration has become a highly political question and an important part of foreign and security policy agendas.

Mobility agreements: an example of more tailored cooperation

The mobility agreements form another instrument for responding to the requirements of the Mediterranean countries to increase the means of legal migration and mobility possibilities, and they could, if translated into reality, prove to be a successful part of the ENP framework. On the basis of a commitment made by each country to meet certain conditions, these agreements take into account the overall relationship with the partner country concerned, which should, at least in theory, take into consideration all the special issues, such as the destabilising effects from the neighbouring countries. However, the EU has been very slow to sign these agreements and there is very little practical information about their usefulness.

Morocco, one of the most advanced Mediterranean countries, signed a mobility agreement with the EU in 2013.22 Interestingly, although this agreement was negotiated and signed by the EU, only a certain number of EU member states became a party to it.23

The objectives of the agreement are nevertheless concrete, such as improving aspects of the conditions of consular services and procedures for issuing Schengen visas and other mobility-related issues that could lead to better opportunities for legal migration. However, before reaching that level, Morocco needs to conclude a balanced legally-binding re-admission agreement with the EU, which includes a requirement to guarantee fundamental rights to migrants. Morocco, just like other Southern Mediterranean countries, has been strongly affected by the crisis in Syria and Libya. Therefore, from the EU’s point of view, the re-admission agreement is crucial, but the potential gains for Morocco remain unclear, as there is no direct link to visa liberation in the event that the re-admission agreement is signed.

Overall, it is hard to imagine that the gains provided in this mobility agreement are attractive enough for Moroccans as the implementation of the agreement is written in a rather vague way: it is conceived as a long-term cooperation framework based on political dialogue with Morocco and the signatories’ intention to meet twice a year at an appropriate level to review the agreement and its annexes (where more concrete actions are listed). However, the mobility agreement says nothing about monitoring these action plan goals or when the mobility agreement will be updated.

The EU also concluded a similarly structured mobility agreement with Tunisia in March 2014. Based on a comparison between the two agreements, differentiation between the two countries is not that clear. However, the annexes include more specific definitions of the sectorial cooperation, which could add the “tailor-made” country-specific promise. But this still begs the question of whether these mobility agreements really fulfil the requirements expressed by the Mediterranean partners to the effect that each of these countries are unique and that their cooperation with the EU should reflect this dissimilarity. Additionally, the ENP partners have clearly expressed their refusal to play the “role of policeman or even of backflow” for immigrants who have transited to their territories, but this is not reflected in these mobility agreements.

Conclusion

This paper observes that the dissatisfaction towards the EU’s Neighbourhood Policy among its southern partners has steadily increased since the uprisings began in late 2010. The European Neighbourhood Policy review has not responded to the crisis in the Arab world sufficiently or swiftly enough. It lacks a comprehensive strategy in response to the greater power shift that is still ongoing in the region.

For decades, the EU had almost exclusively maintained intergovernmental relations with its southern neighbours, most of which were under autocratic rule. With the Arab Spring uprising, many of these old rulers were replaced, and the EU was unable to define how to deal with the new rulers, some of whom represented political Islam. Since the Arab Spring, the southern partners have formed a very mixed group: Some are ruled by remnants of the old regimes (such as Egypt), some are hostile to democratic reforms (such as Algeria), while in some cases the uprisings unleashed civil war and led to failed states (Syria and Libya). Today, Tunisia and Morocco are the only ones that still fit into the EU’s modestly modified ENP framework.24

Given these internal constraints and the turmoil in its southern neighbourhood, the EU has concentrated excessively on the security agenda in its relations towards the region, consolidating “Fortress Europe” instead of being able to concentrate on the needs arising from the southern partner countries that wish to establish more legal means of migration, for instance. As a consequence, fragmentation and diversification are now replacing the notion of a Southern “Neighbourhood”. If the EU wishes to salvage the ENP framework, it should be drastically simplified and complemented by more flexible schemes that truly respond to its partners’ interests and priorities.

Moreover, the EU should critically assess to what extent and under what kind of conditions the ENP framework could deal with migration-related issues. On the other hand, the state-building efforts, such as security sector reform, should again become a top priority in the cooperation with the southern partners, whether within the remit of the ENP, or outside of it. Similarly, the main concrete measure requested by the southern partners – an increase in legal migration to the EU – should also be addressed, although this may prove difficult as it is not actively supported by the member states.

Endnotes

1 Joint Consultation Paper “Towards a new European Neighbourhood Policy” JOIN (2015) 6 Final.

2 Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade (DCFTA) is not analysed here, mainly because none of the Southern Mediterranean countries have concluded this agreement with the EU.

3 EU Commission Communication on “A European Agenda on Migration” COM (2015) 240 Final.

4 The EU’s Neighbourhood Policy has two dimensions: Eastern and Southern, but this paper concentrates only on the latter.

5 COM(2003) 104 Final of 11.03.2003: The Neighbourhood Policy includes two dimensions: Eastern and Southern, but this paper concentrates only on the latter.

6 As stated by Hatem Ben Salem, the former Tunisian Minister Of Education, at an EU-Tunisia Association Council press conference in Brussels, 17/04/2015.

7 A New Response to a Changing Neighbourhood – a review of the European Neighbourhood Policy. 25/5/2011.

8 Berti, Benedetta: After the Spring: State-building processes and institutional reforms: SSN-EUROMESCO joint policy study, March 2015.

9 According to the World Economic Forum, Egypt ranks 117/148 when it comes to basic institutional requirements for competitiveness, such as judicial independence, security and law. Tunisia is ranked somewhat higher, at 73/148. www.worldeconomicforum.org.

10 Transforming Tunisia: The Role of Civil Society in Tunisia’s Transition, Deane Shelly, February 2013, www.international-alert.org.

11 Anette Jünemann: Civil Society, its role and potential in the new Mediterranean context, IEMed briefing paper, 7 May 2012.

12 Kausch, Kristina: The end of the Southern Neighbourhood: IEMed Paper 18, April 2013.

13 www.eeas.europe.eu/ country reports, Tunisia 2014.

14 Transforming Tunisia: The Role of Civil Society in Tunisia’s Transition, Deane Shelly, February 2013, www.international-alert.org.

15 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Communication of Migration 04705/2011 COM (2011/248 final).

16 Amel Azzouz, Secretary of State to the Tunisian Ministry of Development, speaking at FIIA seminar “Challenges and Opportunities in the Middle-East’s Transformation” on 19th March, 2015.

17 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Communication of Migration 04705/2011 COM (2011/248 final).

18 European Parliament resolution of 05/04/2011 on migration flows arising from instability: scope and role of EU foreign policy ( 2010/2269(INI).

19 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A dialogue for migration, mobility and security with the Southern Mediterranean countries 24/04/2011 COM(2011) 292 final.

20 Ibid.

21 Seeberg, Peter, “Learning to Cope: The Development of European Immigration Policies Concerning the Mediterranean Caught Between National and Supranational Narratives”. In Euro-Mediterranean Relations after the Arab Spring (eds.) Horst et al. 2013. Ashgate: Surrey.

22 Council of the European Union, 3/6/2013 “Joint declaration establishing a Mobility Partnership between the Kingdom of Morocco and the European Union and its Member States”.

23 Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK are the signatories of the agreement. Other EU member states can also join this “Joint

Declaration” later.

24 Hinnebusch, Raymond. The Arab Uprising and the Stalled Transition Process. IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook, 2014.