yhteenveto

Maailmankauppa on kehittynyt heikosti talouskriisin jälkeen. Lisääntynyt protektionismi selittää vain pienen osan kaupan heikkoudesta. Talouskasvun näkökulmasta huolta herättää se, että kaupan vapauttaminen näyttää jatkossakin edistyvän hitaasti.

Yhdysvaltain ja Kiinan taloudelliset suhteet eivät rajoitu kauppaan ja toisiinsa linkittyneisiin tuotantoketjuihin. Niitä lujittavat myös rahavirrat ja investoinnit, jotka hyödyttävät molempia osapuolia. Vahva taloudellinen keskinäisriippuvuus tarkoittaa sitä, että todennäköisyys kahden maan täysimittaiselle kauppasodalle on vähäinen. Mailla on yhteisiä intressejä, ja molempia haittaisi kaupan ja muun taloudellisen yhteistyön merkittävä rajoittaminen.

On kuitenkin selvää, että maiden välisissä suhteissa riittää haasteita jatkossakin. Kiinalla on vahva pyrkimys kehittää kotimaisia brändejään ja kasvattaa tuotantoketjujensa omavaraisuutta. Tämän toteutuessa yhä suurempi bruttoarvonlisäys pysyy Kiinassa. Kiinan muuttuva kasvumalli tarkoittaa myös sitä, että maan kasvu hyödyttää ulkomaita jatkossa aiempaa vähemmän. Toisaalta Kiina pitää kiinni vahvasti omista intresseistään ja on ollut haluton avaamaan monia toimialoja kansainvälisille investoinneille. Niinpä Yhdysvaltain ja Kiinan väliset jännitteet todennäköisesti jatkuvat. Niitä voi pahentaa se, että talouskriisi heikensi kasvunäkymiä Yhdysvalloissa, mikä todennäköisesti ajaa maan turvaamaan omia etujaan entistä aktiivisemmin.

Yhdysvallat ja Kiina ovat avainasemassa, kun maailman kauppapolitiikkaa määritellään. Keskeistä on, pääsevätkö maat yli kahdenvälisistä haasteistaan vai ajavatko ne omia intressejään monenkeskisten rakennelmien kautta, joissa toinen osapuoli pyritään ainakin osittain ohittamaan.

Introduction

Trade liberalization has basically stagnated during the last ten years or so and, conversely, the increase in protectionism has received a great deal of attention of late. The financial crisis forced many countries to focus on domestic challenges and turn their back on further trade liberalization. Added to this, the rise of populist parties has provided a further fillip to trade restrictions. Although the rapid rise in the number of trade restrictions explains only a small part of the weakness of world trade since the financial crisis, the role of trade policies should not be underestimated. Indeed, if trade liberalization stagnates or even goes into reverse, it could have a deleterious effect on global economic development.

The two largest economies in the world – the US and China – play a key role in formulating future trade policies at a global level. Although economists generally agree that both countries have benefited from the rapid rise in international trade that took place in the 1990s and 2000s, globalization has also had negative consequences at a more local level. The support for Donald Trump’s protectionist election campaign reflects these concerns.

This briefing paper illustrates the recent trends in world trade and analyses the part played by protectionism in the weak development. The specific aim is to figure out what the future looks like for world trade, and to analyse in particular the bilateral economic relations between the two giants, the US and China.

Rise in protectionism only partly to blame – so far

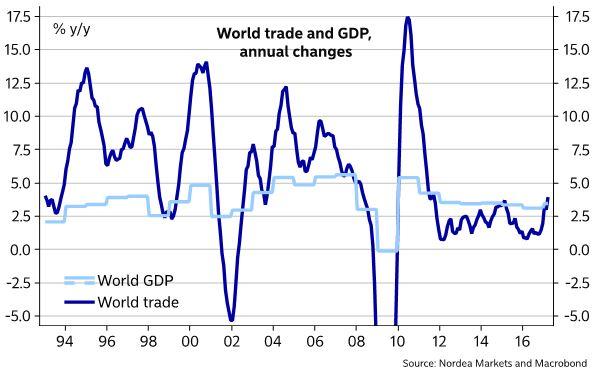

The overall developments in world trade have been surprisingly weak since the financial crisis. Although trade made a quick recovery from the dramatic drop witnessed in 2008-2009, it has not returned to the healthy rising trend seen prior to the crisis. While a part of the weakness is, of course, explained by the generally slow economic growth, world trade has been disappointing even with respect to the global GDP. Prior to the crisis, a 1% increase in the global GDP boosted world trade typically by 1.8%, but recently that impact has halved (Chart 1). In other words, the elasticity between the GDP and trade growth rates has declined considerably.

The most significant reason for the decline in trade elasticity is the slow growth in machinery investment. Investment goods are typically highly trade-intensive and weak investment activity implies slow growth in trade as well. In addition, the geographical composition of growth seen in the post-crisis years – slow growth in the trade-intensive Euro area and fast growth in non-trade-intensive emerging economies – has decreased the growth rates of global trade.

Some of the explanations behind the disappointing developments in international trade are related to the recent trends in globalization. The rapid globalization of supply chains that took place in the 1990s and 2000s has started to slow down. In some cases, supply chains have actually been relocated inside one single country. This may be partly due to the decreasing willingness of countries to be dependent on imported components and parts, which may be further strengthened by the recent trend of rising trade restrictions.

The increase in the number of trade restrictions is hardly surprising as many economists predicted that a wave of protectionism would arise after the financial crisis hit economies in such a harsh way in 2008. The crisis resulted in high unemployment and declining living standards, which had served as a launchpad for protectionist measures a number of times before, and the most recent episode was seen as no exception.

Thus far, countries have refrained from progressing to hardline protectionism and most developed economies have retained their previous low tariff levels. The rise in protectionism has been more technical and indirect in nature as the most frequently used distortions include subsidies to domestic production, localization requirements and the introduction of technical standards. The coverage of these types of measures has been small, amounting to just a few percentages of world trade, which has limited their negative impact on trade and the real economy.1

Chart 1. Sluggish growth in world trade since the crisis

Much more worrying than the rising trend in technical trade restrictions is the fact that trade liberalization has basically stagnated. The emerging economies have not continued to decrease their tariffs closer to the level of the developed economies2 and trade negotiations at the global level are proceeding very slowly, if at all. While some countries have tried to circumvent the blockage in worldwide negotiations by developing bilateral relations, this has turned out to be challenging as well. The bilateral negotiations between the US and the EU, for example, seem to be in deadlock and Donald Trump has already announced that the US will withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which was supposed to liberalize both goods and service trade considerably among 12 countries.3

It therefore seems clear that even if we have avoided a devastating wave of full-blown protectionism, the world economy is losing trade liberalization as a source of growth. Many economists fear that the drag of protectionism on growth is likely to become even more serious in the near future given the global political setup. Last year brought two major events in this regard: the UK’s Brexit decision and the election of Donald Trump as US president.

Trump’s protectionist agenda

Trump’s election campaign paved the way for increasing protectionism. His slogan “Make America Great Again” conveyed the idea of a zero-sum game in the world economy and the importance of the relative position of the US compared to other countries – a radical shift from the earlier way of thinking, where leading politicians recognized the general benefits of trade liberalization at the global level.

Trump’s message was targeted at those American voters who have benefited little from the favourable economic development of recent decades. While globalization has accelerated economic growth by boosting productivity, and has increased welfare at the aggregate level, recent decades are also often associated with rising inequality in developed economies, especially in the US. Furthermore, China’s unforeseen emergence as the leading manufacturing country has certainly created serious disturbances at grass-roots level in many countries.4

Trump’s idea of restoring industrial jobs in the US simply by limiting imports is, of course, appealing at first sight. However, in real life things are far from that simple. It is widely known that a majority of the manufacturing jobs that have disappeared from the US in recent decades is due to technological development, and globalization plays only a limited role. Furthermore, forcing those jobs that have shifted to a low-cost country back to the US would probably only worsen economic productivity in the country.

However, politics is a different ball game compared to economics and it may well be that in order to improve his approval ratings Trump will try to deliver on his promises to voters and take significant steps towards protectionism. During the election campaign he proposed to set import tariffs at 45% for Chinese products and 35% for Mexican products. While Trump considers these measures simple to implement, in practice their effectiveness could remain low as importers may try to circumvent the tariffs. In addition, such tariffs would not be compatible with the existing WTO rules and are likely to cause a wave of counteractions that would also hurt the US economy.

Another option for the US would be to go along with the House Republicans’ proposal for so-called destination-based tax. The new tax system would form a key part of a complete corporate tax overhaul whose main purpose is to encourage US companies to pay their taxes inside the US. However, from the perspective of the international economy, the proposal can be interpreted as a way to increase tax competition between countries, or even protectionism. This is because the proposal introduces a tax on imports, but exempts all export-related income in corporate taxation. This basically increases import prices and lowers export prices. Although basic macroeconomic models indicate that the competitive advantage created by the new tax system would be compensated by a stronger exchange rate, it is not guaranteed that trade flows would remain intact. In addition, another reason for the criticism from other countries is that the new tax system could encourage some companies to relocate their production to the US in order to optimize their taxation. This could have significant and unpredictable effects on the global economy.5

Finally, it is not at all certain whether the new US administration will really turn to widespread protectionism. Trump’s rhetoric has softened considerably since he came to power and his first tax proposals at the end of April did not include the idea of a destination-based tax. However, the withdrawal from the TPP agreement and the requirement to renegotiate the terms of NAFTA signal that the US is, at least, unlikely to push forward trade liberalization in the coming years.

China’s fast-growing influence

As mentioned above, China has been one of the main targets of Trump’s protectionist rhetoric. This is understandable given the major shifts in the world economy and international trade caused by China. China’s rise has been exceptional and the country is currently the largest exporter in the world by far, dominating trade in many sectors (Chart 2).

China’s role in world trade seems to be continuously evolving also qualitatively. The main emphasis of Chinese exports already shifted years ago from labour-intensive sectors such as textiles and toys towards high-technology sectors.6 One factor behind the shift has been the rising wage level, especially in coastal areas, which has pushed labour-intensive production further inland, or to other countries with lower cost levels. The country has also experienced rapid technological progress.

Chart 2. China’s unprecedented rise to become the largest exporter

Along with the technological development, China’s role is also evolving from being part of an international supply chain to an increasingly independent brand-maker and innovator. While in the pre-crisis period, more than 40% of China’s imports were parts and components for the processing sector, the share is now less than a quarter.

This trend is likely to continue in the future. In 2016, China published an ambitious programme “Made in China 2025”, which aims to boost Chinese domestic brands and technology. In practical terms, this would mean that China aims to retain an increasing share of value added from its exporting industries inside the country. Furthermore, China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative is heading in the same direction by improving connections among Eurasian countries in particular, but has often been seen as a way for China to advance its own interests in the area.

China’s strategy has prompted concerns particularly in other Asian countries, which have thus far functioned as major suppliers of components and parts for China’s export sector. If the US really leaves the TPP as Trump has suggested, the initiative to counterbalance the rising power of China in the Pacific area may fail, at least to a large extent.7 This means that smaller economies will remain highly vulnerable to China’s trade policies.

On top of the changing composition in China’s export industry, China’s changing growth model will have an impact also on its imports. Even if imports of many consumer goods are encouraged by China’s rising level of income, the gradual shift from investment towards consumption and a service-based economy is likely to keep import growth tamed. The IMF, for example, forecasts that in the next five years, China’s import volume will grow at only half the speed of GDP growth.8 Thus, this means that even if China has recently been speaking in favour of free trade, the economic realities are likely to imply that China’s future growth will provide fewer possibilities for other countries than many have expected.

Chart 3. US-China trade is unbalanced

Economic links between two giants are tight

Although the obvious conclusion to be drawn from the above is that the aims of the two largest economies are partly contradictory to each other, the two countries also have tight economic relations. As a result, their performance is linked to each other.

Trade inevitably undergirds the relations between the two. Out of China’s exports, a fifth goes to the US, and China is the biggest import country for the US. However, the bilateral trade is seriously imbalanced (Chart 3). In 2016, the bilateral trade deficit amounted to around 2% of the US GDP. Even if international production chains explain almost half of the deficit and the value added retained in China is much smaller than the trade flows would indicate, the trade deficit can still be considered significant and has provoked much criticism in the US since as early as the mid-2000s.

In addition to trade, China and the US have tight investment relations. US companies have substantial foreign direct investment in China, and Chinese companies have recently become more active in investing abroad, not least in the US. A considerable share of US companies’ profits come from abroad, and China is likely to play an important role in this respect.

From China’s point of view in particular, foreign direct investments play a much bigger role than simply providing financing and channels for export. Very often, foreign companies have been an important source of technological spillovers inside China. These spillovers have contributed to productivity developments in China, which increases their importance considerably.

Another link between the two giants is China’s position as one of the biggest foreign creditors of the US federal state. Despite the decline seen recently, China’s holdings of US treasuries amount to more than USD 1000bn, corresponding to 7% of US total debt. If relations between the two countries worsen considerably, China could start fire-selling the bonds and cause a major panic in global financial markets.

China’s characteristics increasingly difficult for the US to tolerate

Even if it is therefore clear that the strong mutual interdependencies do decrease the probability of widespread protectionism, it does not mean that economic relations between the US and China would not encounter considerable challenges in the near future. The two countries are already among the most active users of trade restrictions and also impose them on each other regularly.

One reason for the increasing tensions is that economic growth prospects in both countries are weaker now than they were in the 2000s. The IMF sees US growth for the next five years hovering around 2%, which is considerably lower than during previous decades. At the same time, China’s growth is expected to gradually slow down. Weakening growth prospects are likely to increase general criticism of the prevailing economic conditions and push the country to profit from international relations more than before.

Another fact that could encourage the US to promote its domestic interests is the rising income level in China. During the long WTO negotiations and even in the 2000s, China was still regarded as a developing country where hundreds of millions of people were living in poverty. Integrating the population into the world economy was only fair, and competition between the countries was limited due to the vast difference in their technological level. The rapid rise in both income and technological levels in China has changed the situation. Along with China’s growing size, its increasing role in the international economy will most likely reduce the US tolerance towards the country’s specific characteristics.

One of these characteristics is the very strong role of the public sector in China. The fact that a vast proportion of Chinese companies do not have market-type requirements for profitability has led to excess capacity in many sectors, posing challenges even at the world market level. The financial sector in particular in China is dominated by publicly owned companies, and the US has increasingly blamed the country for using the financial sector as a tool to boost unprofitable investments.

The public-sector dominance is one of the reasons for the US not guaranteeing a market-economy status for China. In accordance with the WTO agreement, China was supposed to gain a market-economy status within 15 years of its accession, but the US has repeatedly refused to grant it. The main motivation for the US not guaranteeing such a status for China is the anti-dumping procedure. If China is not considered a market economy, the US can compare its price level to prices in comparable economies when investigating a possible anti-dumping case. This is important for the metal industries, for example.

The US is also pushing for more openness for foreign direct investments in China. China continues to place numerous limits on foreign investments in many sectors or allow only minority shares for foreign shareholders. Now that Chinese companies have started to increase their foreign investments, many countries, the US included, have started to notice the bias in the openness.

One factor that has diminished in significance in discussions between China and the US is the exchange rate. While a decade ago, China was intervening in the foreign exchange market to keep the renminbi artificially weak, the current pressure is going in the opposite direction. China’s foreign exchange reserves have already decreased by USD 1000bn since 2014 when China tried to prevent the currency from weakening excessively. At the moment, it would consequently be absurd to criticize China for artificially boosting its price competitiveness via the exchange rate.

The exchange-rate discussion was also underplayed when Presidents Donald Trump and Xi Jinping met for the first time in April 2017. According to media reports, the meeting went smoothly and the countries will continue working together to resolve the challenges in the coming months. Some further trade agreements have already been settled since the meeting although the significance of the agreements is likely to be slight. It thus seems that there will not be any immediate shifts in the US trade policy compared to earlier administrations.

Strong interdependence reduces risk of widespread trade restrictions

The near future of international trade does not look very bright. There are many economic factors which imply that a trade boost of the type witnessed in the 1990s and 2000s is not set to return. The further concentration of economic growth on services away from investment and manufacturing, the slowdown in the globalization of production chains, and the rising share of emerging economies, which are less open to trade than developed economies, are likely to slow down trade for many years to come.

The political situation and the rise of populist parties are increasing the pressure on free trade. As the discussion often concentrates on the negative side effects of trade liberalization, traditional parties have difficulties in defending free trade. Pushing for further liberalization is particularly challenging, not least because further steps would imply harmonization of technical standards and would very much extend free trade to the service sector – an area notoriously difficult to liberalize. Rather, the tendency is towards continuously slow progress in free-trade negotiations and increasing technical trade restrictions.

Regarding the future tendency in trade policies, the role of the US and China is incomparable. As we have seen, the two giants have a lot of common interests extending far beyond trade in goods. Strong links effectively limit the extent of possible trade restrictions as such measures would be harmful for both economies. Thus, even if the US is likely to defend its own interests increasingly actively in tandem with China’s rising role and income level, a vicious circle of counteractions is unlikely.

On the other hand, China’s growth strategy, which emphasizes the country’s self-sufficiency, implies that the benefits of China’s strong growth for the outside world are expected to be limited in the future. China will also compete at a technological level increasingly comparable to that of the advanced economies, while lagging behind in reforming its economic structures, due to domestic reasons. This certainly raises concerns over fair competition in other countries, as well as in the US, where domestic interests are being promoted more actively than before due to the fact that the financial crisis weakened growth prospects. This means that the economic tendencies between the US and China will persist.

It will be interesting to see whether the US and China prioritize their bilateral relations or start shunning each other by forming trade blocs on their own. Recent actions – Trump abandoning the TPP, which was once seen as a way for the US to decrease China’s role in the region, and China inviting the US to its One Belt, One Road initiative – support the view that the two economic giants want to cooperate widely in trade policy in the future as well.

Endnotes

1 The recent literature on weak trade developments is summarized in the IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2016, Chapter 3 “Global Trade: What’s behind the Slowdown?” which estimates that protectionism accounts for only a small, albeit not insignificant, part of the recent weakness in world trade.

2 This actually implies that the average level of tariffs in world trade is slowly rising due to the rapidly rising share of emerging economies in world trade.

3 Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the US, and Vietnam.

4 See, for example, Autor, D. H. et al. (2016) The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade. NBER Working Paper No. 20906.

5 See, for example, Auerbach, A. et al. (2017) DestinationBased Cash Flow Taxation, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation WP 17/01.

6 Pula, G. and Santabárbara, D. (2011) Is China climbing up the quality ladder? Estimating cross country differences in product quality using Eurostat’s COMEXT trade database, ECB Working Paper No 1310.

7 The other countries have recently announced that they will continue pursuing the TPP without the US.

8 There are, of course, also contradictory views. Oxford Economics forecasts nominal US exports to China to grow by 8% a year until 2030 https://www.uschina.org/reports/understanding-us-china-trade-relationship last accessed 30 May.