yhteenveto

Intia, Turkki, Brasilia ja Etelä-Afrikka tavoittelevat entistä moninapaisempaa, lännen valtakauden jälkeistä maailmanjärjestystä, jossa niihin ei suhtauduta vain suurvaltojen tukijoina vaan itsenäisinä ja omaehtoisina kansainvälisinä toimijoina.

Maiden ulkopolitiikan tavoite on muuttaa keskeisiä globaalihallinnan instituutioita. Kaikki neljä valtiota havittelevat pysyvää jäsenyyttä YK:n turvallisuusneuvostossa. Saavuttaakseen päämääränsä ne tarvitsevat tukea myös muilta kuin länsimailta, mikä osaltaan vahvistaa tarvetta monisuuntaisille kumppanuuksille.

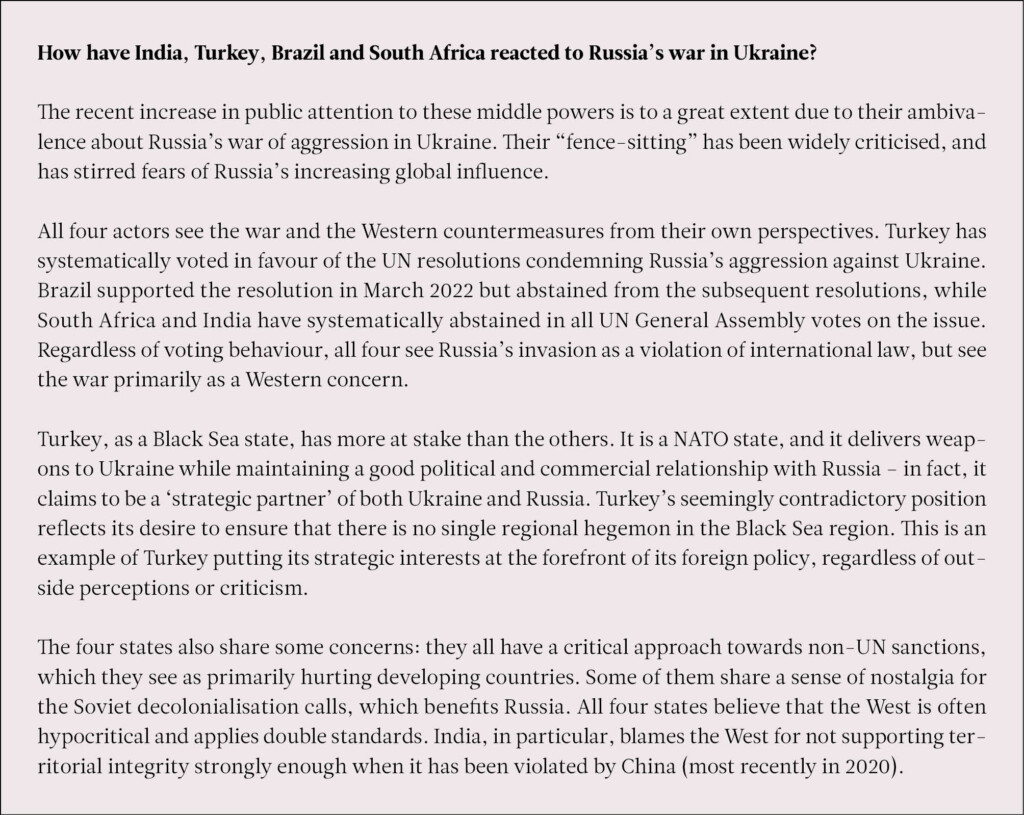

Intia, Turkki, Brasilia ja Etelä-Afrikka tarkastelevat Venäjän Ukrainassa käymää hyökkäyssotaa sekä lännen vastatoimia omasta näkökulmastaan. Ne pitävät Venäjän hyökkäystä kansainvälisen oikeuden loukkauksena, mutta katsovat sodan olevan pääasiassa lännen huolenaihe.

Vaikka nämä neljä maata suhtautuvat länsivaltoihin usein kriittisesti, ne eivät ole lähtökohtaisesti länsivastaisia, ja ne kaikki arvostavat monenvälisiä instituutioita; nelikon ulkopoliittiset tavoitteet ja piirteet tarjoavat EU:lle mahdollisuuksia yhteistyöhön, mutta tämän on tapahduttava aiempaa tasavertaisemmin.

Introduction

Pivot states, global swing states, fence-sitters, polyamorous powers… India, Turkey, Brazil, and South Africa have been given plenty of labels recently.[1] These labels tend to describe more the way the West approaches these states, rather than how they see themselves or their foreign policies.

This Briefing Paper suggests that the analysis of these states should be rooted more systematically in the context of power transition within the global order. While there are great differences in the foreign policies of India, Turkey, Brazil and South Africa, they all share a desire to see a more multipolar, post-Western world in which their ‘great powerhood’ would be recognised by others. They are not completely aligned with nor vehemently against the United States or the ‘West’, but they are not satisfied with being auxiliary powers to bigger players. Instead, they seek to obtain an autonomous role of a global power and a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to prove it.

This paper analyses the foreign policy priorities and concerns of these four G20 members, placing them in a comparative light. The emphasis is on how the states themselves define their international agenda. The four states were selected to represent the world’s emerging powers on the basis of their geographical spread and recent international activity, but the selection should not be seen as definitive or exclusive.

Three perspectives on ‘great powerhood’

The international system is undergoing a structural transition caused primarily by shifts in power balance between different states. Firstly, there is an undeniable power shift towards Asia driven by the economic rise of China, but also of others such as India, South Korea and Indonesia. Secondly, there is a more global power shift comprising several regional centres of power, including actors such as Brazil, Nigeria, South Africa, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Their increased international status is the sum of many internal and external developments: a relative increase in their state power, changing geopolitical constellations, and improved coordination of their policies on the global stage.

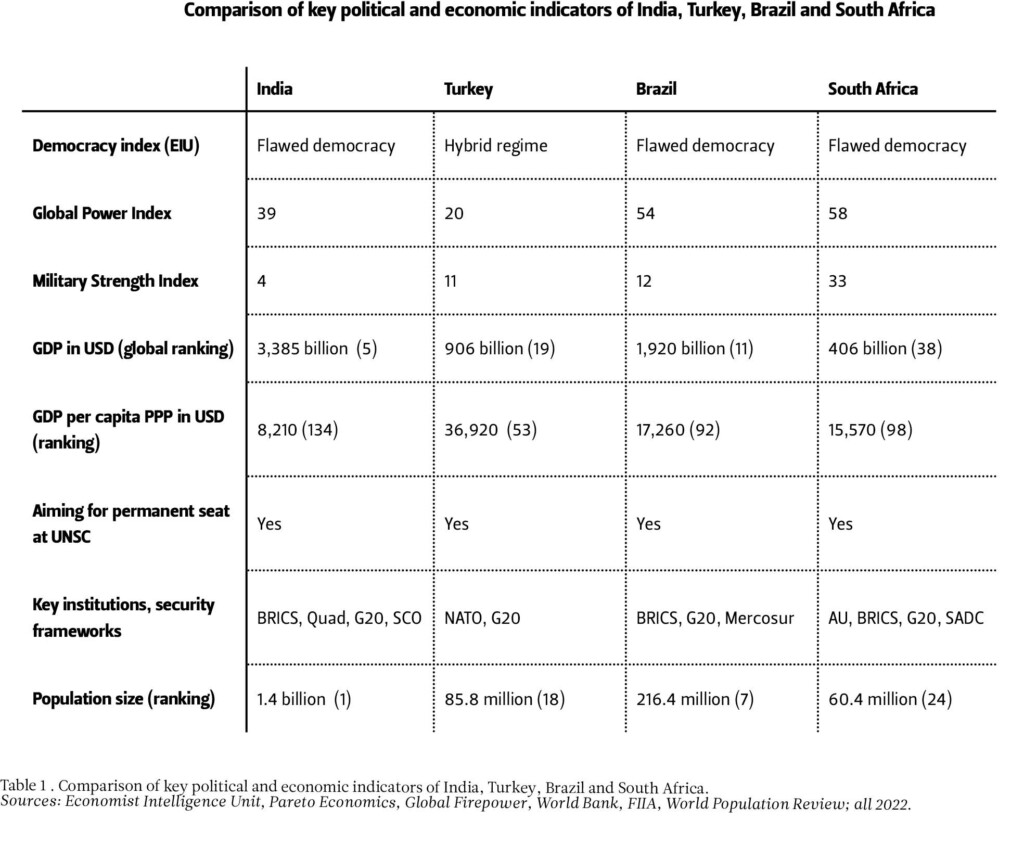

While these broad power shifts are easy to identify, it is much harder to measure and quantify state power objectively. Most global power indexes try to distil a state’s economic, military, technological, demographic, and political power relative to others. In other words, they attempt to quantify national power as a resource. Most of these indexes place emphasis on technological capabilities and economic might, which tend to highlight the capabilities of Western states.[2] In the emerging powers’ discourse, however, the emphasis is often put on autonomy of action as a key characteristic of a great power.

Another way to approach power is to analyse how states actually exert influence and power internationally – in other words, what is the size of their political footprint globally? One could assume that at least in the long run, these two dimensions of power would converge. In reality, this is often not the case: the most important global governance structure, the UN, strongly reflects the global order as it was after World War II, not what it is today. The Western states have also largely been able to maintain their privileged position in the global financial system and markets.

There is also a third perspective to state power: the quality and characteristics of that power. Typically, ‘great power politics’ is associated with zero-sum geopolitical competition, spheres of influence and military power. In comparison, ‘middle power politics’ is taken to mean more ‘benign’ foreign policy: a positive-sum logic and the promotion of multilateral frameworks and cooperation. Middle powers – Canada, Australia, Germany, South Korea and Japan – are states with significant power resources and with a considerable but typically auxiliary role in international affairs.[3]

However, in practice, there is no consensus on which states belong to which group, and different analysts and national traditions highlight different aspects of ‘great powerhood’. When it comes to defining ‘great powerhood’, the economy-driven or military-capability criteria are just one way to approach the matter – for some states, autonomy of action and willingness to use military force may be more important in defining great power status. Some states are content with their respective status and others strive for more power and recognition. Furthermore, a state can seek more recognition through aggression and risk-taking or through institution-building and constructive political incentives.

The states examined in this paper – India, Turkey, Brazil and South Africa – are mostly seen as belonging to the ‘middle power’ category in terms of their power resources and/or global influence, with the partial exception of India (see Table 1). India is often seen as a great power due to its possession of nuclear weapons and its massive population, yet its global influence is still largely confined to South Asia.

However, all four states themselves highlight their great power role, and their current foreign policies are more ‘great power-like’ than those of typical middle powers. They are eager to gain wider recognition internationally as great powers and want to see multilateral institutions transformed to accommodate their enhanced role in world affairs.

‘India first for global good’

India continues its economic ascendancy. It has the world’s fifth largest economy, which is forecast to expand by 7% in 2024 and to grow at least tenfold in the next 25 years. However, while India has a young and highly educated population, poverty reduction remains a challenge – as do the country’s protectionist policies and absence from regional trade integration efforts.

Security threats arising from Pakistan have been a constant in India’s foreign policy. Even so, China is arguably New Delhi’s key security threat, not least due to unresolved border/territory disputes in Kashmir and Northeast India. China is a major supplier of military equipment, economic assistance and major infrastructure projects to Pakistan. Furthermore, China has been expanding its influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region, posing a direct threat to India’s interests in the region and beyond. In terms of military power, India has the fourth most powerful military in the world, with the third highest defence budget and the second largest standing army consisting of 1.5 million military personnel.

India aims to become an acknowledged great power in a post-Western multipolar world order. Its ‘India first for global good’ policy is grounded in inclusivity, and it is wary of Western interference in domestic affairs. India is profiling itself as the voice of the Global South, and as a bridge between the West and the South. This aim is buttressed by a strong civilisational discourse of India’s role as a world teacher (Vishwaguru). India is an active proponent of UN reform and a strong contender for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

India has shifted from an active non-alignment foreign policy during the Cold War to pragmatic multi-alignment in the emerging geopolitical order. While the country has enhanced its security alignment with the West as a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad) and closer relationship with the Australia-UK-US security pact (AUKUS), it also actively takes part in Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) cooperation and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

From the Indian perspective, its multi-alignment is not ‘hedging’, meaning avoidance of taking sides in international disputes and reduction of risks by diversifying fallback positions. Rather, it claims, the policy is about ‘strategic autonomy’.[4] India will act resolutely in international issues that are in its interests and priorities, but not merely because Western states demand it. A case in point is India’s ambivalence regarding the war in Ukraine. Although India admits that Russia has violated international law, it does not see it as a question in which it would need to take sides more actively. Based on its priorities, India has continued trading with Russia – an important fossil fuel and defence industry exporter for India.

Turkey: ‘The world is bigger than five’

Turkey is a ‘trade regime’ with strong export-oriented companies. It promotes free trade arrangements and implements de-regulation policies. The EU has remained Turkey’s foremost economic partner, but it is seeking foreign direct investments and technology transfers from all directions. In terms of GDP, Turkey ranked as the 19th largest economy in 2022. It currently has military bases and troops in seven countries: Libya, Iraq, Syria, Somalia, Northern Cyprus, Qatar, and Azerbaijan. It directly occupies Northern Cyprus and three enclaves in northern Syria. Turkey has the second largest army in NATO, and has significant regional military capabilities. Its main security threats are domestically rooted but subsequently trans-nationalised into organisations such as the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) and the Gülen movement.

Turkey is one of the middle powers critically reflecting on its status in the current international order. It sees its traditional relationship with the West as humiliating and aims to increase its room for independent foreign policy. Whereas the West sees the current deterioration of the so-called liberal world order as threatening, Turkey perceives it as an opportunity. President Erdoğan’s motto – ‘the world is bigger than five’ – is used when criticising the current composition of the UN Security Council. Turkey sees itself as an autonomous actor that does not side exclusively with the West or with the China-Russia axis.

Again, hedging does not fully describe the way in which Turkey conducts its foreign policy: it does not avoid risks in its foreign policy, it bargains hard with all partners and often acts independently of others, even of its allies. Under President Erdoğan, Turkey has re-narrated its state identity as Islamic, presenting itself as the leading Muslim nation. The rhetorical style is anti-imperialist and often underscores Turkey’s role as the ‘world’s conscience’, allegedly defending the poor and deprived nations.

Turkey’s foreign policy style is transactional, and it claims to be “strong both at the negotiation table and in the field”.[5] Turkey can cooperatively advance certain common NATO policies, such as recently sending a peacekeeping force to Kosovo, yet vehemently accuse its allies of arming PKK terrorists or encouraging Islamophobia. The same compartmentalization applies to Russo-Turkish relations insomuch as the two countries’ support for opposing parties, for instance in Syria and Libya, is not allowed to jeopardize their energy and trade relations. In the case of China, Turkey takes a realpolitik stance: China’s economic power is taken as a given and Turkey adjusts its own connectivity projects to those of China accordingly. Turkey’s compartmentalization also allows it to ignore the Uyghur issue with China when necessary.

Brazil’s quest for greatness

Brazil is the world’s 11th largest economy and a country of over 200 million inhabitants. China is Brazil’s largest trading partner by a wide margin. The United States has sought to balance the resulting Chinese influence on Brazil by designating it as a Major Non-NATO Ally. Europe is seeking a similar balance with its Mercosur trade agreement, still pending ratification.

Brazil can play an even-handed geopolitical game because it lacks major external security threats. Criminal networks, especially in the Amazonian borderlands, qualify as the biggest challenge to its sovereignty. While Brazil and Argentina continue to exchange barbs due to the shifting ideological orientations of both countries’ leadership, the prospect of actual military engagement is remote. Domestically, Jair Bolsonaro, who served as president from 2019 to 2022, returned the military to the centre of Brazilian politics, from which his predecessors had successfully dislodged it during the previous three decades.

Brazilian grand strategy points towards a multipolar world, a setting in which Brazil could “assume its greatness”.[6] This quest for ‘greatness’ came from President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, now in his third term in office, early in his first term two decades ago. This vision includes two different elements. First, Brazil needs to propagate a world that is multipolar, lowering the entry point to world power to the extent that Brazil makes the cut. Second, Brazil needs to rise, especially economically, but also as a diplomatic and cultural force, to the extent that others do not question its belonging to such a club of world powers. These two paths, the lowering of the entry point and the elevation of Brazil through recognition, can be followed either in parallel or alternately.

Lula has described the BRICS expansion, for example, as a question of geopolitics rather than ideology. [7] The objective of such pragmatism is the full recognition of Brazil’s global standing through a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Russia has expressed support for Brazil’s inclusion, and China has come to do so too in exchange for an enlarged BRICS, a major goal for China. The goal of a UNSC seat helps explain the “fence-sitter” logic of Brazil’s foreign policy; to fulfil its grand strategy, Brazil needs to have the simultaneous support of all five permanent members of the UNSC.

South Africa: A champion of a fairer world

South Africa is the second biggest and the most developed economy on the African continent. China, the US and Germany are its biggest trading partners. Despite being a regional economic and technological power hub, the worsening electricity crisis, corruption, and entrenched inequalities undermine the country’s economic potential. These internal issues constitute key threats to its stability, alongside regional unconventional security threats such as violent extremism. South Africa’s military capabilities, which are meagre in comparison to the other states discussed here, are primarily geared towards responding to diverse internal and regional emergencies.[8] South Africa actively engages in regional and international peace operations.

South Africa views the shift towards a post-Western world order as an opportunity. Since its transition from the apartheid system in 1994, South Africa has pursued foreign policy with a developmental agenda and a quest for a fairer rules-based world. From South Africa’s perspective, the merits of the Western-dominated liberal rules-based order are mixed. While it shares the commitment to democracy, human rights and international law, it is critical of inconsistently applied rules and norms, and inequality pertaining to global political and economic dynamics. The institutions of global governance and global economic relations need to be reformed. While South Africa’s foreign policy prioritizes African development and an identification with the Global South, neither the country itself nor its continental peers view its foreign policy as primarily representing Africa.[9]

South Africa strives to advance its foreign policy objectives through issue- and interest-based cooperation with multiple powers rather than by aligning itself in either-or fashion between the rival global powers. Legacies of the apartheid era and the relatively peaceful democratic transition also continue to influence South Africa’s foreign policy, for example in its tradition of military non-alignment and prioritisation of peaceful conflict resolution.

There are, however, signs of shifting emphases in South Africa’s strategic partnership leanings: political and security partnerships with other BRICS countries and the Global South in general are becoming more pivotal, while the West is mainly seen through the lens of economic relations. Recently, South Africa’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – such as its refusal to condemn Russia at the UN and its joint military exercises with Russia and China – has caused tensions with the West, illustrating the influence of historical ties in South Africa’s foreign policy and its quest to act as an autonomous power.[10]

Conclusions

The foreign policies of India, Turkey, Brazil and South Africa share some key features. All four states are champions of autonomous and pragmatic multi-alignment, a decolonialisation agenda, and the emerging post-Western and multipolar world order. None of these states are vehemently anti-Western or anti-liberal, and many of them cooperate closely with Western institutions or frameworks. Their approach to foreign policy is interest-driven and often issue-based. While they all value multilateral institutions – particularly in regional settings where they have more influence – they also seek autonomy of action when national interests require it. From their own perspective, they are not ‘balancing’ or ‘hedging’ in their external relations. Rather, their multi-aligned foreign policy is an attempt to establish their own centres of power.

While these states have different historical and cultural backgrounds, they all see the emerging world order as an opportunity to correct humiliation and insufficient international recognition rather than as a threat to their standing. From this perspective, the multi-aligned approach seems highly rational: to transform the current international system, these aspiring great powers need backing from more states than just the Western states.

Together as well as separately, they have been able to strengthen their international standing during the past decade or so. Moreover, the rise of China has indirectly improved the bargaining power of these four aspiring great powers. Their criticism of global governance institutions and Western policies is heard louder and clearer in Western capitals when the fear of “losing them to China” is a plausible – however unlikely – scenario.

This dynamic has been on display in the BRICS. The BRICS summits and cooperation have contributed to the visibility of the aspiring states’ agenda and concerns. Internal tensions certainly exist between the more authoritarian and anti-Western China and Russia, and the more democratic and multi-aligned Brazil, India and South Africa. Thus far, the grouping has served the interests of Brazil, India and South Africa fairly well but, as more states join the group, the future is more uncertain.[11] In any case, the BRICS group is just one vector for pursuing foreign policy for Brazil, India and South Africa. They also cooperate closely with Western frameworks (such as the Quad in the case of India), the US (in the case of Brazil), and the EU (in the case of South Africa).

In sum, this paper has argued that the call for greater global recognition of India, Turkey, Brazil, and South Africa should be taken seriously by the West and the EU. Although these states are critical of the West, they are not anti-Western, they advocate a multipolar world order, and all of them value multilateral institutions. These features offer plenty of opportunities for the EU to engage with them in international relations. This is not to say that the EU sees the four states as easy partners – and they no doubt feel the same way about the EU. The four states all have their own priorities stemming from their history, geopolitical position and economic features, and there is no single appropriate way of approaching them; the EU needs to engage in constructive dialogue with each of them to map where interests align. It is in the EU’s interests to advance global multipolarity – alongside multilateralism – as this also enhances the EU’s own global agency.

Endnotes

[1] See e.g., Matias Spektor (2023) “In Defense of the Fence Sitters. What the West Gets Wrong About Hedging”. Foreign Affairs, May/June, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/global-south-defense-fence-sitters; German Marshall Fund (2023) “Alliances in a Shifting Global Order: Rethinking Transatlantic Engagement with Global Swing States”, May 2023, https://www.gmfus.org/news/alliances-shifting-global-order-rethinking-transatlantic-engagement-global-swing-states; Asli Aydıntaşbaş et al. (2023) “Strategic Interdependence: Europe’s New Approach in a World of Middle Powers”. ECFR Policy Brief, October 2023. https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Strategic-interdependence-Europes-new-approach-in-a-world-of-middle-powers-v1.pdf.

[2] On power indexes and measuring state power, see e.g., Pareto Economics’ Global Power Index at https://pareto-economics.com/global-power-index/; Heim, Jacob L. and Benjamin Miller (2020) “Measuring Power, Power Cycles, and the Risk of Great-Power War in the 21st Century”. RAND. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2989.html; as well as Abbondanza, Gabriel and Thomas Stow Wilkins (2022) Awkward Powers: Escaping Traditional Great and Middle Power Theory. Palgrave Macmillan, p. 6.

[3] Dong-min Shin (2015) “A Critical Review of the Concept of Middle Power”. E-International relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2015/12/04/a-critical-review-of-the-concept-of-middle-power/; Thies, Cameron and Angguntari C. Sari (2018) “A Role Theory Approach to Middle Powers”. Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 40, no. 3 (December), pp. 397–421.

[4] Bajpaee, Chietigj (2023) “The G20 showcases India’s growing power. It could also expose the limits of its foreign policy”. Expert Comment, Chatham House, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/09/g20-showcases-indias-growing-power-it-could-also-expose-limits-its-foreign-policy.

[5] Hurriÿet Daily News (2020) “Turkey would be front line if not strong in Syria: FM Çavuşoğlu”, 10 November 2020, https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-would-be-front-line-if-not-strong-in-syria-fm-cavusoglu-159883.

[6] Brands, Hal (2010) Dilemmas of Brazilian Grand Strategy. Monographs, Books, and Publications. 595. Army War College Press, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/595.

[7] Della Colletta, Ricardo (2023) “Nao estamos colocando ideologia no brics mas geopolitica, diz Lula”. Folha de S. Paulo, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mundo/2023/08/nao-estamos-colocando-ideologia-no-brics-mas-geopolitica-diz-lula.shtml.

[8] Cilliers, J., & Esterhuyse, A. (2023) “Is South Africa’s defense force up for new thinking?”. ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/is-south-africas-defence-force-up-for-new-thinking.

[9] Ishmael, Len (2023) “South Africa: Pursuing Multialignment and Striving for Multipolarity”. Insights, German Marshall Fund of the United States, https://www.gmfus.org/news/new-geopolitics-alliances-rethinking-transatlantic-engagement-global-swing-states/south-africa; Williams, C., & Papa, M. (2020) “Rethinking ‘Alliances’: The Case of South Africa as a Rising Power”. African Security, 13(4), 325–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2020.1871796.

[10] Du Plessis, Carien (2023) “South Africa’s naval exercise with Russia, China raises Western alarm”. Reuters, 17 February 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/south-africas-naval-exercise-with-russia-china-raises-estern-alarm-2023-02-17.

[11] In August 2023, the BRICS group decided to invite Argentina, Egypt, Iran, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to become new members of the group. Turkey has occasionally flirted with the option of joining BRICS, but has not done so up to now.