Sammanfattning

In 2024, elections will be held in Russia, the European Union, and the United States. The elections will carry implications not only for the domestic politics of these three polities but also for the international arena, including the war in Ukraine.

While the Russian presidential election lacks any democratic credibility, Vladimir Putin’s confirmation may encourage him to pursue an even more aggressive military policy. However, this would still be a domestic political risk, and Putin’s primary expectation is that Western aid to Ukraine will wane.

The European Parliament elections are expected to result in a surge of far-right parties, but the EU’s decentralized power structures and consensus-based procedures make sudden political changes unlikely. Enlargement policy will be high on the EU’s agenda in the next legislative period.

In the US, the presidential and congressional elections will see a clash between two very different visions for both domestic and foreign policy. The consequences will be drastically different depending on the outcome of the elections.

Introduction

The year 2024 will usher in an unusual global electoral constellation, as people in three powerful polities will vote on their political leadership. Within only a few months, there will be elections for the Russian presidency (17 March), the European Parliament (6–9 June), and the US presidency and Congress (5 November). Due to the different political cycles, such a constellation is not expected to occur again until 2084.

The three events are, of course, very different in democratic quality: most importantly, while both the EU and US elections offer free and fair competition between political alternatives, Russia has regressed into an increasingly authoritarian system in which the electoral outcome is virtually certain in advance. Moreover, the United States and Russia have strong national capitals, whereas power in the European Union is much more decentralized. Still, in all three polities, the elections will be a defining moment, setting the political course for the coming years – not only domestically, but also on an international scale. Much is at stake, particularly for Ukraine, which is under attack from Russia, depends on support from the US, and has applied to join the EU.

This Briefing Paper takes a comparative look at the three elections and their possible international impact, particularly on the European stage.

Russia

Unlike the EU and the US presidential elections, the Russian presidential election in March 2024 will not be a genuine competition between political alternatives, but a demonstration of Vladimir Putin’s hegemony. As long as the connections with the West are completely severed and the conditions for the opposition to operate within Russia are practically crushed, the Kremlin has no need to worry about the democratic credibility of the election. In this respect, Putin’s press secretary Dmitry Peskov’s unexpectedly candid remark that the election “is not really democracy, it is costly bureaucracy” was revealing.[1]

The upcoming presidential election will probably break previous records of dishonesty, as has been the case in recent years. From the 1990s to the present day, almost every Russian election has seen a deterioration in various aspects compared to the previous election. This decline is evident in the competitiveness of elections, campaigning rules, timing, election observation, candidate filtering, repression of the opposition, as well as falsified results.

Over the past five years, the Kremlin has rapidly lost its remaining confidence in the equilibrium that prevailed between tightly controlled presidential elections and freer regional elections. After the regional elections between 2017 and 2019, when the opposition achieved partial successes, the regime became increasingly repressive towards local-level politics as well. Paradoxically, this demonstrates the democratic potential of elections through the threat experienced by the regime. The fewer genuine alternatives there are in elections, the more the Kremlin seems to fear the threat posed by even formal alternatives.

The context of the ongoing war and Putin’s de facto dictatorship give rise to a question: Why does the Kremlin still want to hold elections with diminishing credibility, which could easily be cancelled under the pretext of national security and unity, for example? Despite this uncertainty, speculation that the September 2023 local elections would be cancelled did not materialize. On the contrary, they were even held in the partially occupied territories in Ukraine despite being a complete sham.[2]

The mobilization of voters dependent on the state budget, representing the vast majority of Russian voters in previous elections, will be taken to the extreme next March by authorizing military units to act as election officials. This will ensure the turnout of hundreds of thousands of war recruits, as their conditions for refusing to vote are weak.[3] The large-scale use of electronic voting also provides effective means for the manipulation of the results and turnout in a covert and controlled manner. In the 2023 regional elections, electronic voting was used in 24 out of Russia’s 85 regions, including the partially occupied regions in Ukraine. Electronic voting will likely be expanded even further in the next presidential election.[4]

It is obvious that citizens’ trust in the meaningfulness of the election is irrelevant. What matters is the impression that the Kremlin gives of its readiness to hold elections, thereby reflecting its strength. Cancelling elections would be an indication of the regime’s weakness, not because it fears the outcome, but rather because it would signal the inability to organize the formal setting for legitimizing itself and demonstrating its strength. A highly illustrative example was the virtual referendum held in 2020 on amendments to the constitution, despite the difficult Covid situation.

Although opposition to the war has thus far posed no risk to Putin’s position, the lack of military victories means that passive approval of the war is largely dependent on securing citizens’ sense of a tolerable life beyond the war. The election and its self-evident outcome are intended to underline the sense of the resumption of normalcy.

For the Kremlin, it is crucially important to seal the necessity of Putin’s existence and debunk any speculation about his declining status and health. This will be the major message for the West as well. On the one hand, it is reasonable to assume that the current need to balance between military policy and normalcy might disappear after the election. The smooth implementation of the election may strengthen the regime’s confidence to pursue a more determined and aggressive war policy, eliminating the threshold for a new wave of mobilization.

On the other hand, the available data on public attitudes towards the war indicates an increased willingness to enter into negotiations instead of continuing the war.[5] Although the negotiations in this case are most likely understood as an adaptation to the Kremlin’s conditions, there is no widespread enthusiasm among Russians for Putin’s militaristic policy. In other words, ending the war would not cause widespread discontent among citizens, quite the opposite. In this regard, pursuing a military breakthrough with a new mobilization after the presidential election would be a major domestic political risk, as there is no quick solution in sight to citizens’ concerns about the rising cost of living. The Kremlin’s heavy investment in the war budget certainly does nothing to ease these concerns.

Moreover, with the election becoming an increasingly closed authoritarian ritual, Putin’s position may not become more secure. On the contrary, when Putin was elected for the current presidential term in 2018 with a landslide victory, this was quickly followed by an unprecedented drop in his approval rating.[6] If the now assured victory were to be followed by a similar setback – for example, in the event of an economic shock that would require Putin’s authority to resolve – the Kremlin would hardly be in a position to remedy the situation with a new geopolitical manoeuvre due to the prolonged and resource-consuming war in Ukraine.

Thus, it is likely that Putin will try to ensure the preservation of the current situation on the war front after his re-election, avoid excessive domestic political risks, and rely increasingly on the hope that Western support for Ukraine will wane.

European Union

About three months after the Russian election, the election to the European Parliament (EP) will take place on 6–9 June 2024, followed by the appointment of a new European Commission and a new president of the European Council.

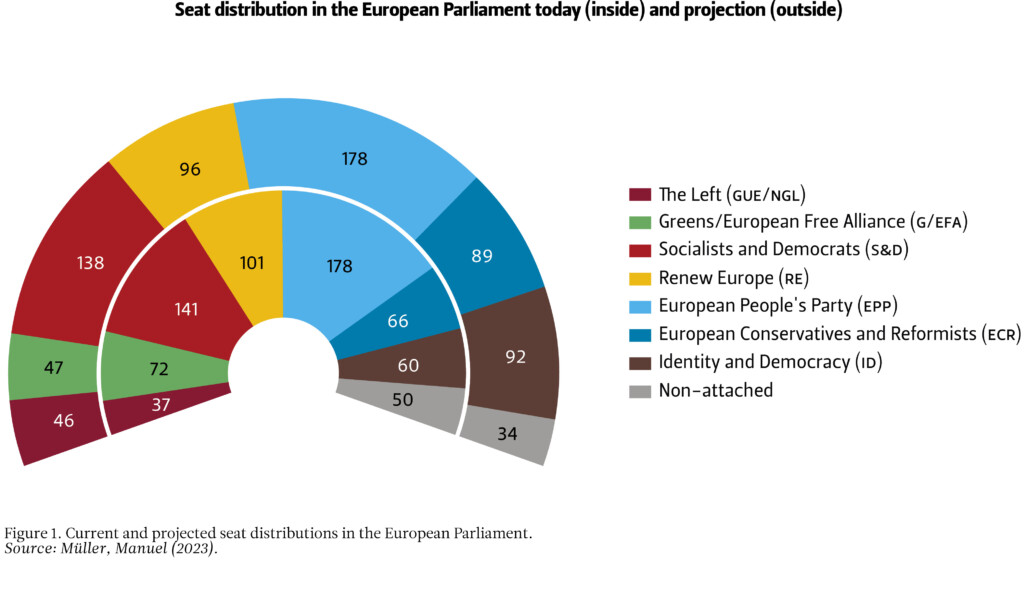

Because EP elections are fair and free, their results are open. Current seat projections (see Figure 1) predict a historic surge for far-right and populist parties. Together, the two far-right groups – the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID) – could win around a quarter of all EP seats, their highest combined share ever. At the same time, the combined share of parties to the left of centre could fall to an all-time low.[7]

Even so, structural aspects of the EP’s functioning make it unlikely that the election will lead to any sudden political changes: the EP does not have the government-opposition dynamic of national democracies, but rather a system of variable majorities formed by large cross-party alliances. Most decisions are taken based on an informal “grand coalition of the centre”, consisting of the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP), the centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D), the liberal Renew Europe (RE) and the Greens. Despite the far-right surge, this “grand coalition” will retain a solid majority in all EU institutions.

Nevertheless, the elections are likely to shift the political power balance towards the right. During the last legislature, a centre-left alliance of Social Democrats, Liberals, Greens and the Left served as an alternative to the “grand coalition” on certain issues. If this alliance loses its majority, this will indirectly strengthen the EPP and possibly impact policies like climate protection, where major differences have recently emerged between the EPP and the centre-left. Some decisions in the next term could also be taken based on an alliance between EPP, Liberals and ECR, or even between EPP, ECR and ID. Still, such forms of cooperation are likely to remain occasional and issue-specific, and will not replace the “grand coalition” as the main basis of majority formation in the EP.

Another factor limiting the direct impact of EP elections is the strong role of member states’ governments in EU decision-making: the EP is involved in almost all EU legislation but must always compromise with the Council. The position of member states is even more dominant in foreign, security and defence policy, which is largely governed by intergovernmental procedures. In recent years, however, the European Commission has also increased its influence in this area, for example in the preparation of sanctions and support measures towards third countries, as well as in enlargement policy.

The appointment of a new Commission after the EP elections will therefore also have a major impact on the EU’s external relations. To be elected, the Commission president will need the support of a majority in both the EP and the European Council, which may lead to complex post-electoral negotiations.

As has been the case since 2014, the European parties will present lead candidates for the Commission presidency during the campaign. So far, no candidates have declared their intention to run. However, if current Commission President Ursula von der Leyen should want a second term, she is almost certain to be nominated as the EPP candidate. If the EPP then emerges as the strongest party (as predicted by seat projections), she stands a good chance of staying in office. In any case, the EU’s strongly consensus-based procedures ensure that the next Commission president will again be a centrist figure acceptable to all parties of the “grand coalition” as well as a majority of the national governments.

In parallel with the election of the Commission president, member states will also appoint a new president of the European Council and a new High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, the latter being subject to confirmation by the EP. Traditionally, these “top jobs” are balanced in terms of regional origin (northern/southern, western/eastern, and large/small member states), party affiliation (EPP/S&D/RE), and gender. With NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg’s term ending in October 2024, the selection of his successor might also be part of this balancing act. All these appointments are likely to bring new faces and new emphases, but no fundamental policy disruptions.

After the election of the EU top jobs, the other members of the Commission are proposed by the national governments and approved by the EP. Here, a shift to the centre-right is likely, given that more member states are now governed by the EPP than in 2019. However, the number of far-right commissioners will remain small, as the ECR and ID are represented in only a few national governments. Moreover, the allocation of portfolios is a prerogative of the Commission president, and politically extreme commissioners are less likely to be given important areas of responsibility.

Finally, the institutional renewal will be accompanied by the definition of political objectives for the next half-decade. At the beginning of the institutional term, documents on upcoming priorities are published by both the European Council (“Strategic Agenda”) and the Commission president (“Political Guidelines”). In addition, the main political groups in the EP could negotiate a formal “coalition agreement”, as they already tried unsuccessfully to do in 2019.

For 2019–24, the EU’s priorities have focused on digital and green transformation, as well as enhancing its geopolitical capacities. All these issues are likely to remain central, as will migration and industrial policy. Still, the main topic of the debate on post-2024 priorities will be the twin agenda of enlargement and internal institutional reform.[8] Even if they are not at the centre of the electoral campaign, discussions on the preconditions, roadmap, and timetable for the accession of new member states – particularly Ukraine – will start immediately after the European elections at the latest.

Overall, the 2024 EP elections are likely to bring a surge of far-right and populist parties, but not to an extent that would affect the functioning of the EU institutions based on the traditional informal “grand coalition”. The increased presence of far-right parties could have a policy impact, especially if centre-right parties try to appease far-right voters, for example on migration or climate policy. However, on major issues such as support for Ukraine or the enlargement and institutional reform agenda, the EU’s supranational institutions – the EP and the Commission – will almost certainly stay the course. Political risks in this regard remain more likely to emanate from the Council, especially when unanimity is required and individual member state governments can block common positions.

United States

The most consequential election of 2024 will be the US presidential and congressional election in November. Even though the presidential candidates have not yet been chosen, it seems almost inevitable that American voters will be choosing between two profoundly different visions for the future of their country.

On the Democratic side, President Joe Biden is running for a second term. His victory in the primary seems a foregone conclusion, unless his health deteriorates so dramatically that he decides to withdraw his candidacy or is no longer able to serve. Biden, 81, is the oldest sitting president in US history, which raises concerns regarding his future physical and mental condition even though he is not currently known to have any serious health problems. If Biden withdraws or becomes incapacitated after the primaries, the Democratic National Convention decides his replacement. If this happens before the electoral college casts its votes on 17 December 2024, the replacement could be anyone the party chooses, regardless of whether they participated in the primaries. If Biden wins but is incapacitated after the electoral college vote, Vice President Elect Kamala Harris becomes President.[9]

On the Republican side, former president Donald Trump is without question the most likely candidate. Despite having numerous primary challengers with bona fide political and conservative credentials and despite having been indicted on 91 counts in four criminal cases, Trump has maintained a commanding lead in the polls. However, it is unclear what will happen to his candidacy if he is tried, found guilty and sentenced to prison before the election. The likelihood of this scenario is difficult to assess, as the trials have yet to begin and Trump’s lawyers are making every effort to delay them.

While a rematch between Biden and Trump is not yet a certainty, a contest between two fundamentally different visions is almost guaranteed. One of Trump’s strongest challengers, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, is in many ways ideologically aligned with Trump, and if Trump were to exit the race, DeSantis would most likely inherit enough Trump voters to win the nomination. At the time of writing, former South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley is challenging DeSantis for second place in the polls, but as her political vision is markedly different from those of Trump and DeSantis, it is difficult to imagine her winning over more Trump supporters than DeSantis.

In the field of foreign policy, both Trump and DeSantis have isolationist tendencies in the spirit of Trump’s “America first” slogan. They have both appeared uninterested in aiding Ukraine, and they place considerable emphasis on countering China. They are unappreciative of the rules-based international order and its institutions, and critical of NATO and European allies. They tend to question or deny climate change. Biden, contrarily, will remain a staunch European and Ukrainian ally, perceive NATO’s security guarantees as ironclad, and consider defending the rules-based international order to be a vital US interest. He will seek to maintain a dialogue with China and view climate change as an existential threat. Any conceivable replacement of a notional incapacitated Biden would also differ starkly from Trump and DeSantis. Amongst topical foreign policy issues, the Israel-Hamas war is an exception in that the US seems poised to support Israel regardless of who wins the presidency.

Biden cherishes the role of the United States as a beacon of democracy for the rest of the world. Trump, in contrast, has a long history of showing respect and admiration towards autocratic leaders. In his 2024 campaign, some of his own pledges have had an authoritarian undertone. Trump has plans to use the Justice Department to seek revenge against his political opponents, fire federal workers for political reasons and replace them with loyalists, and consolidate power in his own hands.

As things stand at the time of writing, both Biden and Trump appear to have a good chance of winning the presidency, and the outcome of the presidential race is impossible to predict.

Elections for the US Senate and the House of Representatives will be held in connection with the presidential election. Their outcome will also have foreign policy implications and a substantial impact on the President’s ability to govern. As with every Senate election, only one third of the seats are in play. In 2024, this gives the Republican party a significant advantage, as more Democrats than Republicans are up for re-election, and several seats that Democrats are defending are considered competitive.[10] Hence it is likely that the Republicans will succeed in taking control of the Senate.

In the House, all seats are in play every two years, making the result harder to predict, but the Democratic party has a much better chance of winning the House race than the one for the Senate. As a consequence, control of Congress may be split between the two parties, making it harder for the President to reach their political goals, regardless of which party they represent. However, it is also entirely conceivable that Republicans might win all three races, giving a Republican president a strong mandate and an excellent opportunity to shape the future of the country. With their difficult path to control of the Senate, Democrats are much less likely to achieve the desired trifecta.

If Biden wins the presidency, his ability to support Ukraine and Israel will be contingent upon Congress, which has the power to appropriate funds for doing so. At the time of writing, there is much more Republican opposition to supporting Ukraine in the House than in the Senate. In this regard, a Republican-controlled Senate might well prove a more reliable ally to Ukraine than the current Republican-controlled House. However, if Republicans control both chambers of Congress, providing aid to Ukraine may prove extremely difficult. Conversely, American support for Israel is a priority for both parties.

If Trump or DeSantis is the next president and chooses not to aid Ukraine, Congress will be powerless to force his hand. Congress may appropriate funding for aid, but the President has the power to withhold it. Similarly, if a Republican president pursues an anti-NATO agenda, there is little Congress can do. It is unclear whether Congress could stop the President from leaving NATO altogether, but even if it did, it might not matter much. The President could undermine the deterrent power of NATO’s security guarantees simply by declaring that under their command, the US would not honour its commitment to NATO’s Article 5. They could also change the European security situation profoundly by closing down American military bases in Europe and moving troops and military equipment away from European soil.

Conclusions

The combined effect of the Russian, European and American elections on international relations and the war of aggression in Ukraine will be enormous. If the Russian election somehow fails and weakens Putin, European voters resist the populist temptation, and Americans choose Biden and give the Democrats solid control of Congress, this outcome will guarantee staunch Western support for Ukraine and American support for all of Europe. In the best-case scenario, it might even lead to a just and lasting peace in Ukraine.

If, on the other hand, Putin’s war policy becomes even more aggressive after his nominal re-election, the surge of the far right complicates majority building in the European Parliament, and Americans elect Donald Trump and a Republican Congress, the future looks bleak for Europe. Trump’s interest in presenting himself as a global “dealmaker” might prompt an emboldened Putin to suggest some kind of US-Russia agreement at the expense of Ukrainian and European interests. In the worst-case scenario, Trump will not only cut off aid to Ukraine but also withdraw the United States from NATO (or otherwise undermine the alliance), while internal divisions and fear of a populist backlash will stall the EU and block its enlargement and institutional reform agenda.

In reality, the outcome is likely to be somewhere between these extreme scenarios. Although the Russian election is almost guaranteed to be a success for Putin, it might not make him strong enough to pursue a more aggressive phase in the war. And while populist and far-right candidates may well make gains in the European elections, the “grand coalition of the centre” will almost certainly retain power in the EU, making any sudden disruptions in either domestic or external policy unlikely. The outcome of the American election is the most open of the three. One conceivable scenario leaves the world with an aggressive Russia, a largely unchanged Europe, and a Europeanist United States led by Joe Biden together with a Republican Senate and a Democratic House of Representatives. However, it is equally conceivable that in 2025, the United States will be led by Trump and a Republican Congress, turning inward or focused on China, and leaving Europe alone to support Ukraine.

Endnotes

[1] RFE/RL’s Russian Service (2023) “Kremlin Spokesman Claims Putin Will Easily Win Reelection Next Year”. Radio Liberty, 7 August 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-peskov-interview-democracy/32536544.html.

[2] Matveev, Ilya (2023) “Putin’s Electoral Theatre: Past, Present and Future”. Russian Election Monitor, https://www.russian-election-monitor.org/putin-s-electoral-theatre-past-present-and-future.html.

[3] Agentsvo (2023) “Na vyborakh prezidenta zasekretyat «golosovaniye stroyem» v voinskikh chastyakh”. 24 October 2023, https://www.agents.media/na-vyborah-prezidenta-zasekretyat-golosovanie-stroem-v-voinskih-chastyah/.

[4] Zavadskaya, Margarita (2023) “Russia’s 2023 September Elections: A Dress Rehearsal for Vladimir Putin”. SCEEUS Voices on Russia No 2, 27 October 2023, https://sceeus.se/en/publications/russias-2023-september-elections-a-dress-rehearsal-for-vladimir-putin/.

[5] Levada tsentr (2023) “Yesli by na etoy nedele V. Putin…” Konflikt s Ukrainoy: otsenki oktyabrya 2023 goda, https://www.levada.ru/cp/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/21.-Eksperiment.png.

[6] The reason for the drop was a highly unpopular pension reform, the implementation of which required Putin’s public support for the decision.

[7] E.g. Müller, Manuel (2023) “European Parliament seat projection (November 2023): EPP takes big lead – historic shift to the right possible”, Der (europäische) Föderalist, https://www.foederalist.eu/2023/11/ep-seat-projection-november-2023.html.

[8] Karjalainen, Tyyne (2023) EU enlargement in wartime Europe: Three dimensions and scenarios. FIIA Working Paper 136, https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/eu-enlargement-in-wartime-europe; Müller, Manuel (2023) EU reform is back on the agenda: The many drivers of the new debate on treaty change. FIIA Briefing Paper 363, https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/eu-reform-is-back-on-the-agenda.

[9] Karmack, Elaine (2023) “What happens if a presidential candidate cannot take office due to death or incapacitation before January 2025?” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-happens-if-a-presidential-candidate-cannot-take-office-due-to-death-or-incapacitation-before-january-2025/.

[10] Blake, Aaron, and Nick Mourtoupalas (2022) “Senate Democrats had a good 2022. The 2024 election could be brutal”. Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/12/08/2024-senate-map/.